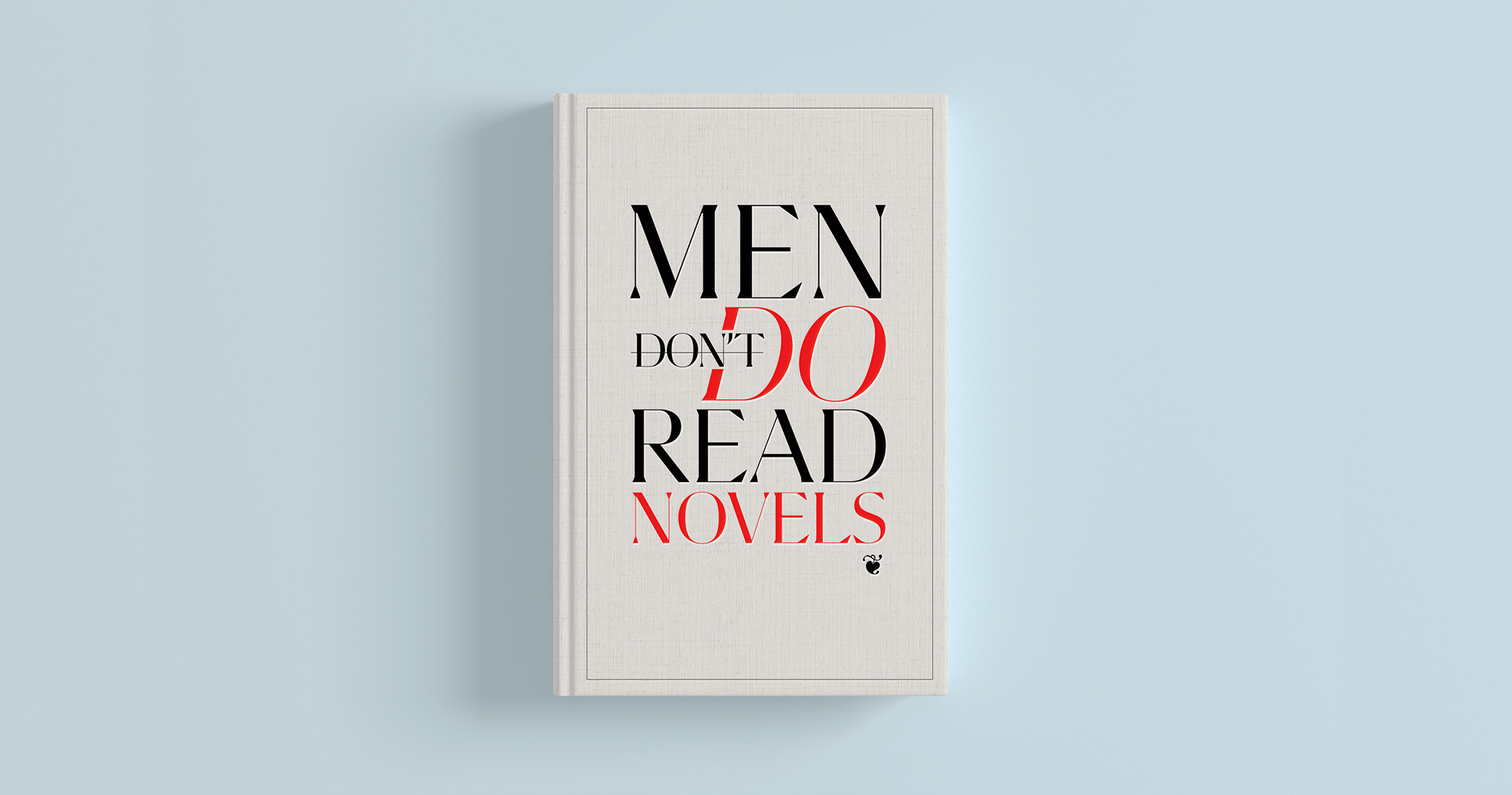

Is Sally Rooney changing men’s reading habits?

What we choose to read often follows gender lines, particularly for men. But as Esquire columnist Ben Jhoty has discovered, if your reading habits have a conspicuous gender slant, you are likely missing out

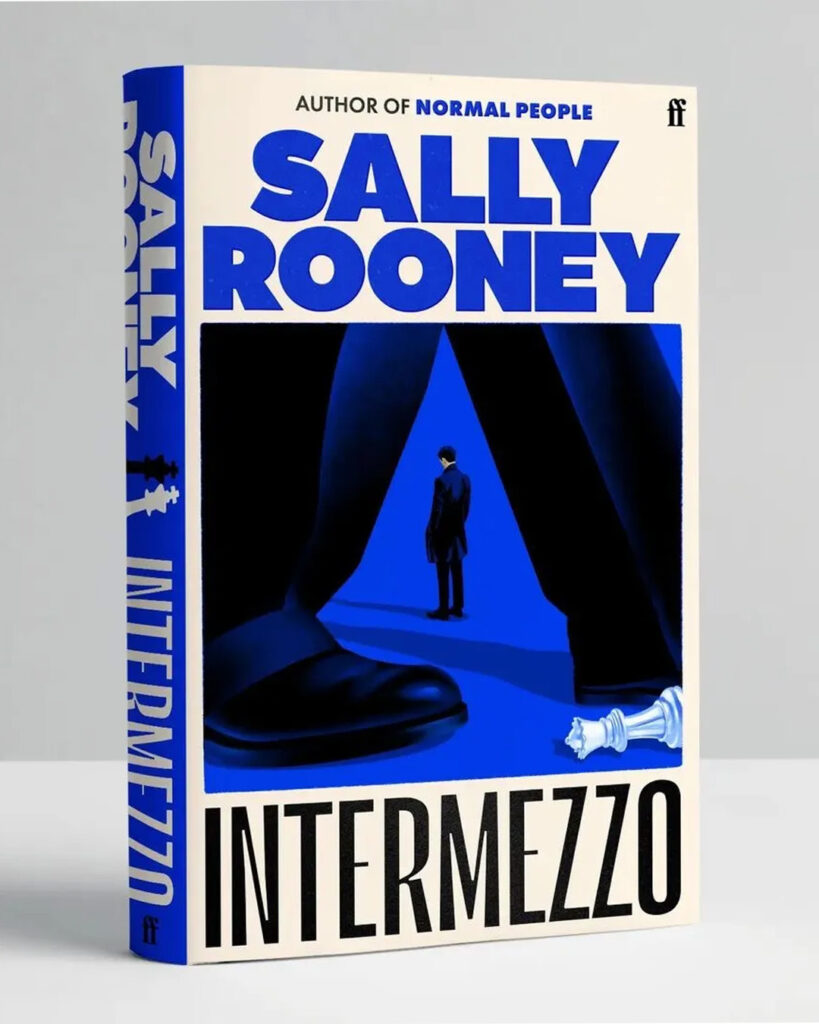

ONE OF THE joys of reading is that every so often a book or an author comes along that changes the way you look at the world. For me, it was the 2018 sensation Normal People by Sally Rooney, a book that served as my gateway drug to a greater appreciation of female authors and a broader reckoning about why I read in the first place.

Of course, the Irish author’s books carry the patina of coolness that comes with being the reigning literary ‘It girl’. As gateway drugs go, Rooney is probably akin to cocaine; her claustrophobic tales exploring Millennial angst around sex, class, friendship and politics certainly seem to have narcotic-like effects on many young women.

I became a fan after watching the TV adaptation of Normal People, starring Paul Mescal and Daisy Edgar-Jones, during lockdown. Prior to that I hadn’t heard of Rooney, but so affecting was the Hulu series, that I felt compelled to seek out the book upon which it was based. That then led me to read Rooney’s debut novel, Conversations With Friends (2017) and the follow up to Normal People, 2021’s Beautiful World, Where Are You?

Soon I was researching Rooney’s back story – I was intrigued that she’d once been the no. 1 university debater in Europe and got her break by writing a non-fiction piece about her time ‘spitting’ coruscating watertight arguments at other nerds. I am now keenly anticipating her latest novel, Intermezzo, out September 24.

After Rooney, I began seeking out other female authors. In the past year or so I’ve read All Fours by Miranda July (a hilariously funny and decidedly weird tale about one woman’s rage against the spectre of menopause), Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin, Yellowface by Rebecca F Kuang, Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason, Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens by Shankari Chandran and The Fraud by Zadie Smith, among others. Apologies for the flex, but it’s crucial to the thesis.

In the same period, I only recall reading one or two books by male writers – one of which, All the Beautiful Things You Love (recommend!) by Esquire columnist Jonathan Seidler, has a female protagonist. As a reader, I would be unrecognisable to the person I was 10 years ago.

In fact, I remember a now rather cringey discussion around that time with a bunch of male colleagues – you know, bookish types – about female authors. None of us read, or at least admitted to reading, many books by women. In fact, I’m ashamed to say the conversation was somewhat dismissive. Each of us was able to cite one lone book – “Well I did read . . .” Often it was something acclaimed, in most cases shortlisted for the Booker Prize or equivalent, the gloss of literary cachet seeming to legitimise the otherwise puzzling decision to read a novel by a woman.

To wit, I could really only recall one book – Annie Proulx’s The Shipping News, which I’d only read because a girlfriend was reading it and I needed to pass time on a Greek ferry. I don’t recall any of us reading less august titles by female authors, which we, as a group, felt occupied a domestic milieu we found dull and repellent. One guy said something to the effect of, “Chicks’ books have too much description. Too much interior.” I had found Proulx’s prose to be extraordinary in its vivid descriptions of the weatherbeaten Newfoundland landscape and the oddballs who populate it. But it hadn’t led me to read more Proulx.

I should add here that the decision to largely read male authors wasn’t a conscious one, at least on my part. I was rather surprised at the monolithic nature of my historical bookshelf. If I was a chauvinistic reader, it wasn’t deliberate, though admittedly, when it comes to bias, intent is often beside the point.

As a kid, I had read a lot of Enid Blyton and Roald Dahl and didn’t really distinguish between them (interestingly, they’ve both since been criticised for propagating racist and sexist stereotypes) – I just wanted to be entertained. But I suspect that as I got older, I may have fallen prey to a common affliction among young male readers, which is self-actualising or ego-centric driven reading. You seek out books that accord with your self image. That might lead you to try and tick off the ‘Classics’ or celebrated books by literary heavyweights – I went through a big ‘giants of 20th century American fiction’ phase – John Updike, Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, et al. While books by these authors are celebrated for a reason, a lot of the time you can find yourself reading them mostly to say that you’ve read them. Aside from Jane Austen or the Bronte sisters (who I had read and enjoyed in school), the literary pantheon, at least pre-1950, is largely a male-dominated arena. This is, of course, a reflection of the times and the opportunities available to women in those times.

In my twenties – aside from The Shipping News, which again came with the imprimatur of literary cache – I doubt I would have read many other female authors. Looking back, it was a rather dull time in my reading history. What had once been a source of delight and wonder as a kid, had become something of a chore, as I resolutely kept seeking out books I believed to be edifying, based either on an author’s reputation or a novel’s critical acclaim.

In hindsight, Zadie Smith’s White Teeth probably should have been my gateway to female authors. I saw it everywhere in bookshops in the early aughts and must have picked it up a dozen times. But it wasn’t until last year, with my new unblinkered reading glasses on, that I grabbed it from a street library and sat down to read it. I promptly devoured it, revelling in the depictions of the multicultural tableau of 1980s London and Smith’s scalpel wit. But I do wonder if I’d read White Teeth 20 years ago, whether it would have led to the Rooney-inspired awakening I’ve experienced lately, or if I would have been unable to get past my chauvinistic, books-as-merit-badges mentality.

So, what could lead a guy to read more books by women? In my case there were two drivers. Firstly, streaming channels, hungry for content, are gobbling up the rights to books by female authors like Liane Moriarty and Rooney. As I did with Normal People, many of us are probably more likely to seek out a book if we enjoy a series.

The other factor I’d point to is the rise of Kindles and electronic readers. While many joke that the cloak of anonymity offered by a Kindle has led to an explosion of erotic fiction, mostly among women, allowing them to enjoy a bodice-ripper on the bus without blushing, I have noticed my reading has become broader and less performative in the Kindle age.

Where once I might have lugged around Infinite Jest or Blood Meridien (the former I never got close to finishing), ostentatiously whipping them out on the train, these days I’m more likely to read a Rooney or a Moriarty on my Kindle app. That’s led to me downloading stuff I actually want to read, rather than books I feel like I have to read or ones that speak to some kind of idealised self-image. More often than not, that’s led to reading and enjoying more books by women. It’s worth noting I’m also enjoying reading more than I ever did in my twenties – hence my year-long hot streak.

Is there a difference between books written by men and women? In terms of the raw mechanics of the prose, I don’t think there’s a lot to distinguish them. While we can’t really blindfold readers with books the way we do quaffers with wine tasting, if you remove an author’s name, I think many of us would struggle to identify the gender of the writer. Seeing the author’s name or their pic on the back of a book creates expectations and colours our experience, allowing us to conclude that a book “was obviously” written by a man or a woman – nom de plumes regularly mess with reader’s preconceptions. Without a gender lens you would likely have a purer reading experience, though perhaps there’s a difference in the treatment of sex scenes – sometimes scenes written by male authors can feel like they were written with a solitary hand on the keyboard.

You might also say the subject material is a giveaway – if the book is historical fiction, for example, or an airport spy thriller, perhaps you’d be inclined to believe it written by a woman or a man, respectively. But I suspect that judgment would be based on expectation rather than the nature of the writing itself.

I discovered, through Rooney, that I like reading about the interpersonal dynamics and interior musings that accompany relationships between young, hip millennials in cities like Dublin. I’ll probably keep seeking out, or the Kindle algorithm will suggest for me, similar books. I can’t honestly say that I’m going to go out of my way to read historical novels about hitherto uncelebrated female protagonists in 19th Century Denmark or Hamptons-set murder mysteries. And I probably won’t be pre-ordering any Booker shortlisted novels – with a record five of this year’s nominees being female, the odds are those will have been written by a woman. I will still let my taste largely govern my choices. But if I get a good recommendation about a book of the type I’ve just mentioned – as I did with July’s All Fours – I’ll dive in, irrespective of the author’s gender or the subject matter. All that matters is that the book is a good read.

It’s probably sad that it’s taken me this long to wise up to the pure wonder of words, regardless of who wrote them or where they come from. As I’ve discovered, when you choose to let curiosity guide your choices and do your best to silence conscious bias, your world opens up.

Once that happens, you can’t rule anything out, or write it off.

Related: