What happens when technology leaves us behind?

We talk a lot about technology becoming obsolete, but less about what happens when it makes us obsolete. In this week's edition of Winging It, Jonathan Seidler wonders whether we no longer have enough time to 'get with the times'.

Jonathan Seidler is an Australian author, father and nu-metal apologist. You may have read his memoir, caught his compelling live performance at this year’s Sydney Writers’ Festival, or noticed his distinct eyebrows on the street. He has some interesting things to say about music, fatherhood, Aussie culture, mental health and the social gymnastics of group chats. This is his column for Esquire.

Recently, I had a phenomenal customer service interaction at my local butcher. The butcher has stood there at the bottom of my street for a million years; it’s run by two charming blokes, one of whom is definitely past retirement age. This man of the better vintage — let’s call him Dan — has yet to fully get his head around Electronic Funds Transfer at Point of Sale machines, which are designed for elder millennials like me who no longer have time for things like tactile buttons.

Dan punched in the damage for my weekly order of beef sangers and I tapped my card, oblivious to the fact that he’d added a few zeroes by accident and I’d just been stung a cool $980. Having realised his transgression about two minutes before my bank did, Dan chased me down the road to apologise. We spent the next half hour trying to figure out how to reverse a machine he barely understood in the first place, and the whole encounter got me wondering about men and obsolescence.

Men of my generation grew up in the golden age of computer technology, which is to say when you could still take the machines apart. I have fond memories of blowing into Nintendo 64 cartridges to rid them of dust, messing around with RCA cables, physically installing CD burners and extra RAM into our family PC. I both set up and broke the first broadband connection in our house. For kids of the ‘90s, learning basic code and how computers worked was right at the forefront of culture. The Internet wasn’t just arriving at our homes, it was also on our TV shows and in our films. The future was tech and we were basically living its evolution in real time.

“Technology dates all of us, but it used to be that you could viably get with the times in enough time that nobody would notice. These days, that’s becoming harder and harder to pull off.”

It’s possible that Dan the butcher experienced this feeling once, too. He probably spent his teenage years learning exactly how his car worked and has likely never once called for roadside assistance. Maybe he sent his younger brothers cryptic messages over fax and typed Morse Code into walkie talkies. Technology dates all of us, but it used to be that you could viably get with the times in enough time that nobody would notice. These days, that’s becoming harder and harder to pull off.

The easiest thing for me to do would be to laugh at Dan and his inability to work a touchpad. I did at the time, because it stopped me realising that I’d inadvertently spent a grand on raw meat. But the truth is, I’m not even half of Dan’s age (I asked). And despite literally being a child of the Internet, I’m already behind the eight ball.

I was once paid to teach others how to use social media, but three new platforms have launched in the past two years and I honestly have no clue how they work. I haven’t figured out how to ask ChatGPT to finish this column or Midjourney to design a photorealistic image of me riding a polar bear, shirtless with a rippling six pack, to accompany it.

We talk a lot about technology becoming obsolete, but less about what happens when it makes us obsolete. Tech isolation can lead to loneliness, which we now know can be more dangerous to men than smoking or obesity.

“Within the next decade (or sooner), we’ll find ourselves as passe as the MiniDisc, with detrimental effects on our ability to connect with one another.”

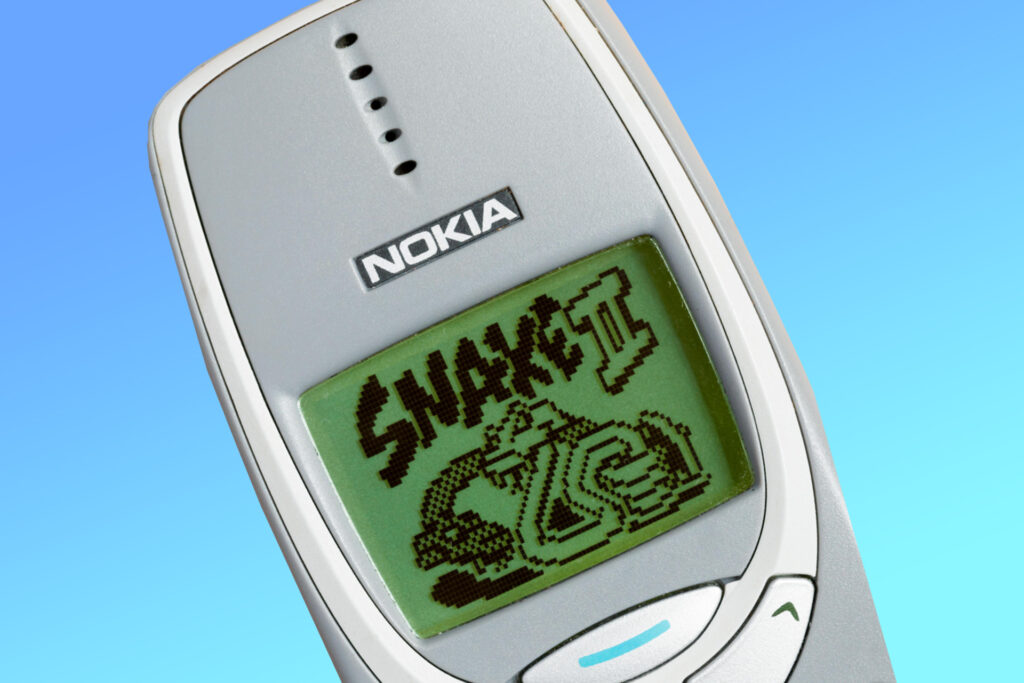

My grandmother is in her 90s and still uses a Nokia. She doesn’t have an email address. That means if she wants to see a new photo of our daughter, she needs to wait to see me so I can pull it up on my iPhone and show her. Not only does this sever her from the zeitgeist, but it disconnects her from her biggest social network: her family.

Of course, she still has a functioning phone — and landline — and uses it to call me all the time. She is from a pre-SMS generation; from Dan the butcher’s generation. Most guys I know don’t pick up the phone, unless it’s to call for roadside assistance. The things that stand in for talking to another person — memes, DMs, watching IG stories, tagging mates on ironic Betoota Advocate posts — are all products of our time. But even that time is shrinking. Old mate Dan has lived his entire life knowing how to carve, store and cook an animal, but I’ve already given up trying to figure out TikTok.

This uneasiness is compounded by a generational shift towards solo living, as we rely on the Internet of things to stand in for the comfort and madness of a house full of people. Australians are marrying later (if at all), living longer and having fewer children. When the current communication systems we take for granted are overhauled, likely within the next decade (or sooner), we’ll suddenly find ourselves as passe as the MiniDisc, with detrimental effects on our ability to connect with one another.

There’s a classic Simpsons episode in which Principal Skinner wonders if he is out of touch, only to decide that it’s in fact the schoolchildren under his watch who are wrong. As we age, we learn the joke is in fact on both parties, as it is on any of us who think we will remain on top of tech forever.

Talk it over with me this weekend. I weirdly have a lot of sausages to cook.

Jonathan Seidler is an Esquire columnist and the author of It’s A Shame About Ray (Allen & Unwin).

Like all proper columns, this one will be back next week. You can see Jonno’s first column for Esquire here.