Is 'doomslang' making us all numb?

Dystopian jargon is taking over the way we talk. But the constant conjuring of End Times is having surprising, unintended — maybe even dangerous — consequences.

I NEVER thought the end of the world would sound so casual.

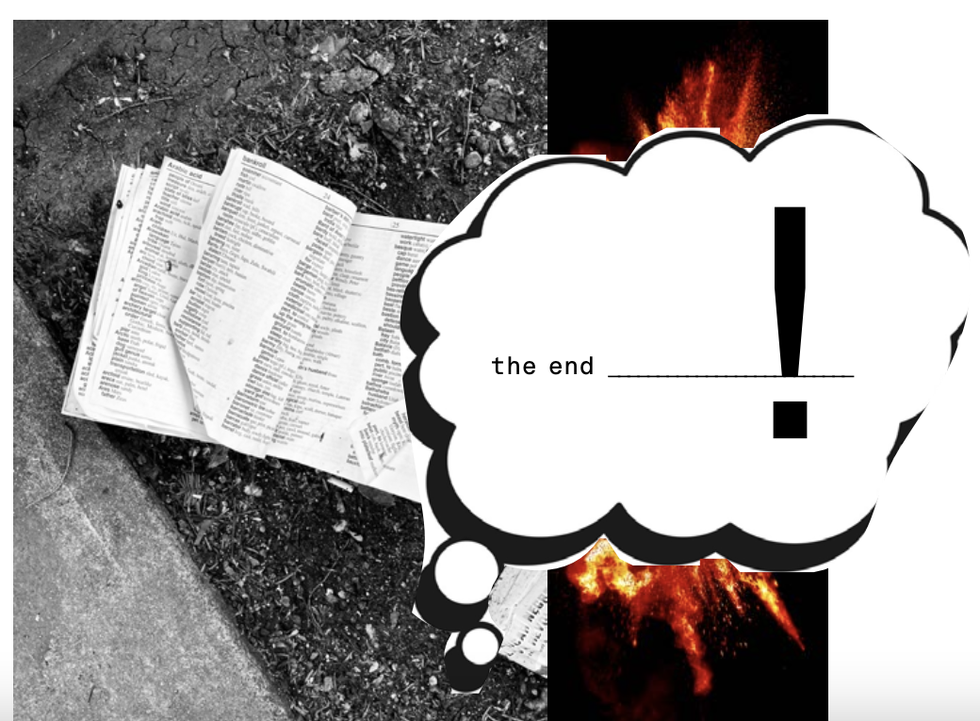

“How are you? Aside from the world burning and all.” This has become my go-to pleasantry – the default, dystopia-flavored greeting I use on Zoom calls, emails, and catchup texts with old friends. It isn’t just me: Ever since the Trump presidency, End Times vernacular seems to have trickled its way from fringe conspiracy forums into jocular chitchat among well-cushioned urbanites. In 2024, conjuring catastrophe in quotidian conversation is practically good manners. Openers like “Did you have a nice weekend?” are followed by the obligatory “I mean, other than the slow creeping demise of the planet.” Social media is awash with doom-themed memes (the “This is fine” dog engulfed in flames; a screen grab of Leslie Knope from Parks and Recreation saying, “Everything hurts and I’m dying”; a pleasant woodland background overlaid with “I’m thinking of joining the cicadas this summer and just screaming for six weeks straight”), emoji combinations (🧟♀️🦠💀🌎🔥⏳🥲), and colloquialisms (“dumpster fire,” “hellscape,” “hate it here lol”). It all seems to suggest that The End will arrive any day now… and yet, everyone is being weirdly chill about it.

I’ve been calling it “doomslang” – this use of informal jargon invoking the apocalypse. I started to look into it more closely while writing a new book, The Age of Magical Overthinking, which explores cognitive biases in the Information Age. One of the chapters addresses declinism, the widespread (and often distorted) perception that society is getting progressively worse in every way and there’s no going back. I was interested in the role of language in this fatalistic outlook. What does doomslang say about our collective mental state? What happens to us when we slang-ify mass misfortune, perhaps only as a macabre bit at first, but then with such cavalier frequency that it renders each of us the boy who cried apocalypse?

According to language experts, the past decade has produced a “bumper crop” of catastrophe-related neologisms. Like “doomscroll,” a verb that emerged in 2018 meaning “to obsessively check online news for updates, especially on social media feeds, with the expectation that the news will be bad.” There’s also “bed rotting,” the most recent doomslang term to have earned an official Dictionary.com entry, which lexicographer Kory Stamper defined as “the practice of spending many hours in bed during the day, often with snacks or an electronic device, as a voluntary retreat from activity or stress.”

End-of-days idioms are also showing up around the world. In Argentina, “disociando” (to zone out during stressful situations) enjoyed a spike amid the tumult of the country’s 2023 presidential election. Also in 2023, the Society for the German Language chose “krisenmodus” (crisis mode) as Germany’s word of the year, explaining, “There have always been crises. But it feels like there is so much crisis [now] … Between apathy and alarmism, it is difficult to find an appropriate way of dealing.”

“Doomslang feels so normalized,” echoed writer and content creator Aiden Arata, whom Mashable.com christened the “Meme Queen of Depression Instagram.” Arata’s corner of the Internet features a surplus of terms that center on “rotting,” “spiraling,” and “casual annihilation language,” including ‘Guess I’ll die,’ the more sinister ‘Guess I’ll kill myself,’ and the handy abbreviation ‘kms’ for when you want to die but don’t want to type a full sentence.

More palatable versions of doomslang have made their way into advertising copy. From fast-food chains to high fashion, brands have spent the last 15 years commodifying the apocalypse. In 2012, Carl’s Jr. debuted its “End of the World” hamburger. The same year, the Zombies, Run! fitness program hit the App Store, and Durex ran a condom ad with the tagline “The end of the world shouldn’t be the only thing coming.” In 2013 (the same year the “This is fine” doggo showed up), we saw the launch of boutique home-goods brand Calamityware, which boasts a collection called Things Could Be Worse. Three years later, artist duo Thomson & Craighead released a high-end Apocalypse fragrance, spawning sardonic headlines like The Guardian’s “I sniffed the end of the world, and it smells like bile and dread.”

There’s irony to doomslang, of course – a comical juxtaposition of panic and banality. The gallows humour can serve as a coping mechanism. As Arata put it, “The Internet has this dual effect of showing us an unprecedented array of horrors and also reminding us that we are in many ways powerless to stop them.” A hopeful take is that doomslang provides a vessel for that cognitive dissonance and a space to place our unease. Faced with so many doomy atrocities, exchanging a bit of facetious slang allows us to acknowledge our despair and then subvert it in a way that can feel empowering, or at least less lonely.

What happens to us when we slang-ify mass misfortune?

Feelings of impending doom, and the language that goes along with them, are hardly new to our paranoid species. Humans have been spiralling about catastrophe – and then dismissing or making light of it – ever since we started making End Times predictions that didn’t come true. “We’ve always talked about the horrors awaiting us all. It seems to be a pretty common human response to gestures broadly,” said Stamper, who found records of doomslang dating back centuries: Throughout the 1600s, individuals who got overly excited about prophesying The End were nicknamed “screech owls,” “ravens,” or “croakers.” In the 18th century, they were known plainly as “prophets of doom.” In 1941, science fiction author Lester del Rey gave us the term “doom-monger,” meaning “someone who tries to make people believe that something very bad is going to happen, usually when this is not necessary or reasonable.” The similar label “doomsayer” arrived in 1954. And in the early 1960s, we got “catastrophise,” a verb describing the act of viewing a situation as worse than it is.

For most of history, doomslang came and went in cycles, according to spikes in cultural anxieties about economic failure, overpopulation, etc. The difference is that in the modern age, disaster always hangs in the ether, like background noise. “Now it’s sort of semipermanent,” said Eddie Yuen, coauthor of the book Catastrophism: The Apocalyptic Politics of Collapse and Rebirth. Yuen credits doomslang’s ubiquity largely to climate change, an undeniably real apocalyptic scenario (unlike, say, Y2K). And of course during the pandemic, doomslang felt like the only appropriate way to talk about the world. “The pandemic actually created our own apocalypse, so how did we deal with that? We made jokes about it,” commented social scientist Laura Myers, who studies crisis communication at the University of Alabama.

But our mediums of communication also play a role in accelerating doomslang. Starting with the dawn of 24/7 broadcasts in the 1980s, disasters became ubiquitous in the news. Now social media makes round-the-clock calamity even less avoidable. It’s no secret that algorithms reward extremes, because they’re engaging. “And what’s more extreme than the end of the world?” said Yuen. “It makes sense that apocalyptic narratives are going to rise to the top.”

But what goes up must come down: After apocalypse rhetoric inevitably comes trivialization. Myers explained this process in the context of “disaster fatigue.” As she told me, “Our systems are not built to take a constant onslaught of bad news, especially if it has the potential to affect us or our loved ones directly.” The relentless stress leads to fatigue and then complacency. Over time, ennui sets in (not unlike it did, for instance, in the 1840s when false prophet William Miller forecasted multiple raptures, convincing his followers to flee their homes and slaughter their animals on date after date, only for nothing to come to pass).

These constant waves of alarm and fatigue are evident in our vocabularies. Terms like “doomscroll” and “bed rot” underscore our fraught relationship with technology, representing both “the overwhelm of bad news through our phones and the use of our phones to escape from said overwhelm,” Stamper said.

Doomslang also takes different forms depending on your politics. Yee-Lum Mak, a rhetoric scholar and the author of Other-Wordly, pointed out that she mostly hears doomslang among highly educated folks under 35 from “reasonably comfortable backgrounds.” She noted the left-leaning tint to much of this language – e.g., “You know how it is in our neoliberal dystopia” or “How are you holding up under late-stage capitalism?” Mak said that some speakers might see it as “politically irresponsible” not to acknowledge the state of the world, even casually. Doomslang could serve as “a small act of resistance to groups they oppose, like climate change deniers or politicians averse to climate legislation.”

But not every doomslanger is in Mak’s algorithm. Compare progressive speakers’ jokes about the brain-eating zombie virus that is America’s Fox News to the alt-right’s “wojak” and “doomer” memes. Originating on 4chan, wojak is a simple outlined sketch of a man, symbolising melancholy and loneliness. Its cousin, doomer, depicts the same character beanie-clad and smoking a cigarette. According to The Atlantic reporter Kaitlyn Tiffany, the doomer meme represents young men who “are no longer pursuing friendships or relationships, and get no joy from anything because they know that the world is coming to an end.”

At worst, the panic that doomslang reflects (and reinforces) could send a user down a conspiratorial rabbit hole. Before they know it, they’re earnestly logging onto PrepperTok, Amazon Prime-ing go-bags for when “Day X” finally arrives. On the far-right extreme, “accelerationists” actually want to bring a violent end to democratic society, and they employ a version of doomslang – say, “The storm is coming” in Game of Thrones font – to convert others to that mentality. (Alarming as this far-right dialect of doomslang might be, Yuen said that its influence should not be overstated. “A problem with right-wing movements is they don’t play well with others,” he assured. So while their memes are worth clocking, especially when they seep into mainstream circulation, there’s little threat that their users will be able to organise well enough to drown out, say, Greta Thunberg’s climate messaging.)

Another pessimistic interpretation is that the blasé hyperbole of doomslang risks pulling focus from the measured action items of crisis communicators, like the National Weather Service and the CDC. In the face of real catastrophe, the best and most human solution is to come together. But doomslang individualises the end of the world. It turns it into a marketing moment, a viral opportunity, a “me problem.”

How can experts break through the noise to activate people in the face of true calamity? If your entire feed suggests that everything sucks and there’s nothing to be done, or if everyone’s distracted by some “social catastrophe” like Taylor Swift’s relationship drama or Barbie not receiving enough Oscar nominations, and all the while disaster disinformation permeates our feeds, like Sharpiegate (Donald Trump’s 2019 false prophecy that Hurricane Dorian was coming for Alabama when it wasn’t), how can we distinguish what’s worth our concern? And what can be done about it?

“We’ve got to get people to be able to critically evaluate information,” Myers told me. Where climate change is concerned, amid the memes and the ironic pleasantries, Myers suggests keeping up with local and national broadcast meteorologists, who can provide the most accurate intel about climate impacts on our environment, infrastructure, and health.

Beneath the levity, doomslang may actually be a bid for human connection. “We might worry about this kind of flippant language desensitising people to heavy concerns,” Mak said. “But I think underlying it all is the feeling, for many people in these generations, that they’ve always lived in a politically unstable world… and they hold little power compared to the huge corporate and political forces that shape those conditions.” Sharing a quip about the oceans swallowing us whole could be an expression of solidarity both with the populations most vulnerable to the impacts of end-time events and others who feel equally helpless against them.

In the end, doomslang is not making us inert, and we don’t need to stop using it. Attempting to halt or manipulate language change is a futile effort anyway, as any linguist would tell you. But becoming aware of the conditions that created this vernacular might help us take it with a grain of salt. As Aiden Arata advised, “Obviously there is the risk of someone not receiving help because they’re like, ‘I want to die’ and everyone is like, ‘LOL.’ Laugh with your friends, and then check on them!”

In her studies of crisis management, Myers has found that in the wake of an emergency, first responders’ go-to mode of discourse is often to make jokes about it – sometimes really dark jokes that would perturb the public if they overheard them. It’s not their way of avoiding catastrophe, but rather their way of dealing with it. We may be seeing something similar with doomslang speakers – such as groups of young environmentalists who might exchange a few irreverent “This is fine” memes in between bringing climate lawsuits against massive oil companies. With optimism, Mak offered, “The same people talking facetiously about the apocalypse may also be the ones banding together to slow our roll towards it.”

Ultimately, doomslang is both an angsty gag and not a gag at all. Perhaps learning to stomach that sense of in-between, linguistically and otherwise, is what will help us all make it through.

A version of this story originally appeared on Esquire US

Related:

Ralph Lauren has always been the King of quiet luxury

Would you live in a Mercedes-Benz, Lamborghini or Aston Martin home?