In his campaigns, Giorgio Armani showed us how to get dressed

The louche tailoring of the Italian designer Giorgio Armani has become shorthand for a fashionable kind of armour. But it was his images, captured over half a century, that have proven to be the ultimate lesson in living in style

IT’S UNUSUAL FOR clothes to stay in their context. Usually, a designer’s vision of their wares – no matter how much was spent on runway shows, styling or campaigns – ends at the point of sale, giving way to the needs of you and me. Rare, then, is the designer whose clothes we seek out to fulfil certain needs; that the louche tailoring of Giorgio Armani has been what his customers have found comfort in – with their ease of movement, strength in proportion and dignity in understatement – for half a century. While the fashion industry has likened the man himself to an emperor, with his vast business and omnipresence, Armani, who died today at 91, has been a sage to those who approach style as a daily study. And a sage needs his texts.

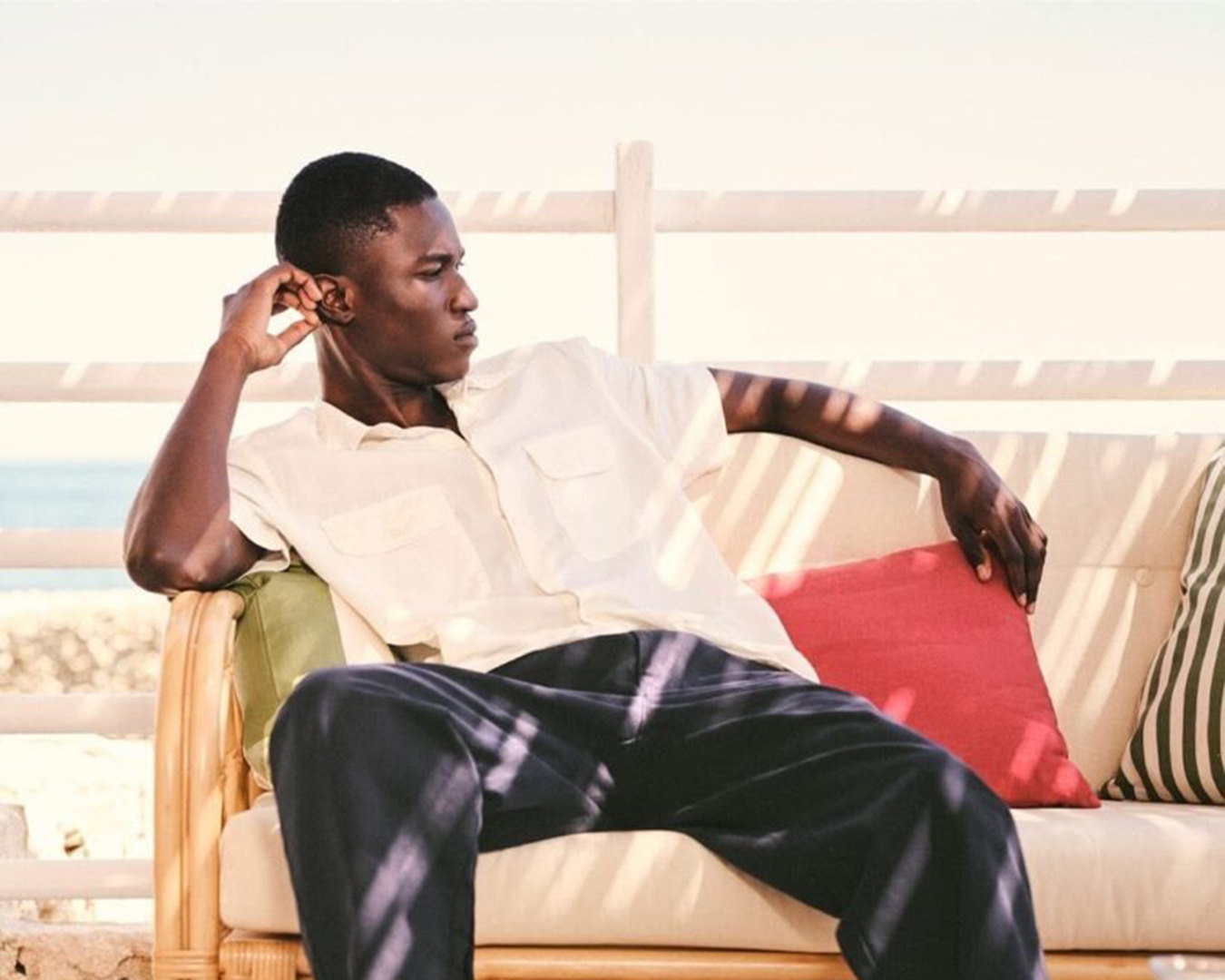

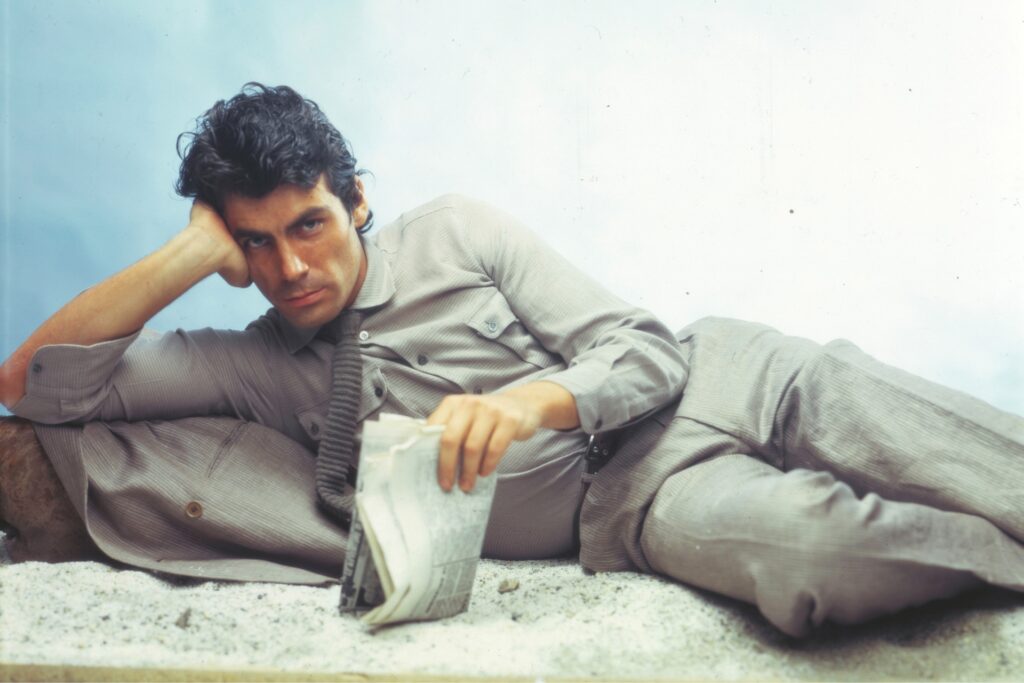

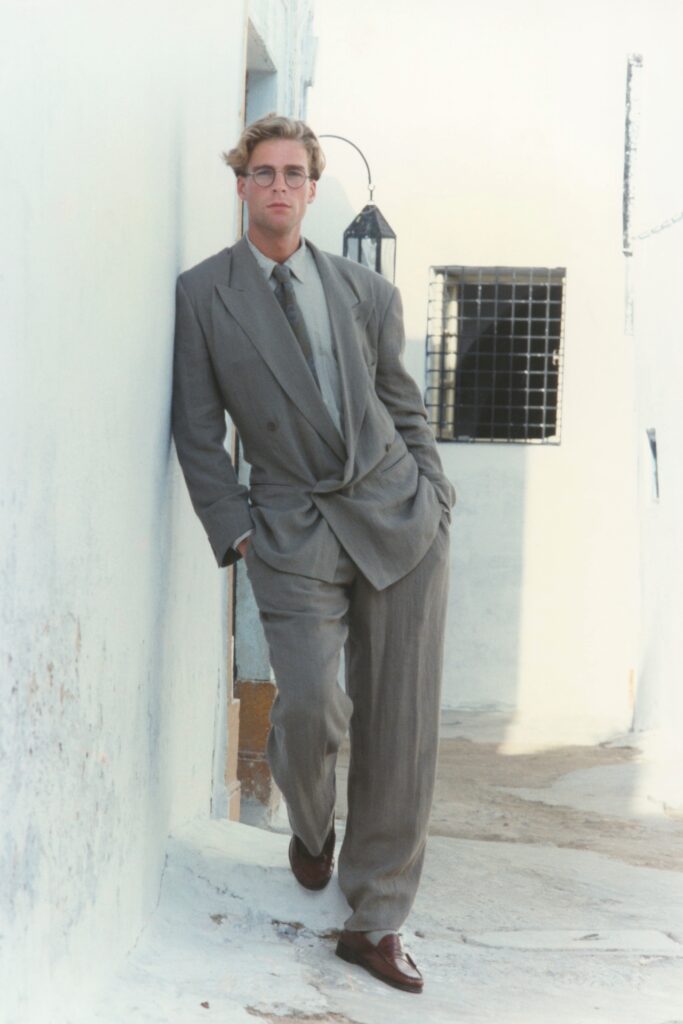

Since the Italian designer founded the brand in 1975, some of his most studied texts have been his campaign images plastered onto billboards, printed in magazines and, later, posted to social media. But what Armani devotees pore over isn’t your usual fare of model-in-designer-clothes. Trying to describe his campaign images is like dissecting a film still. But here goes with one example: a group of yuppies in matching grey suits and red-and-yellow ties are spending their lunch break reading the newspaper. While each man shows his own response to the written facts, with one looking especially irritated as he reaches for his ear, their coolness as a unit is seen in the drape of their trousers and jackets as they settle in for the news of the day.

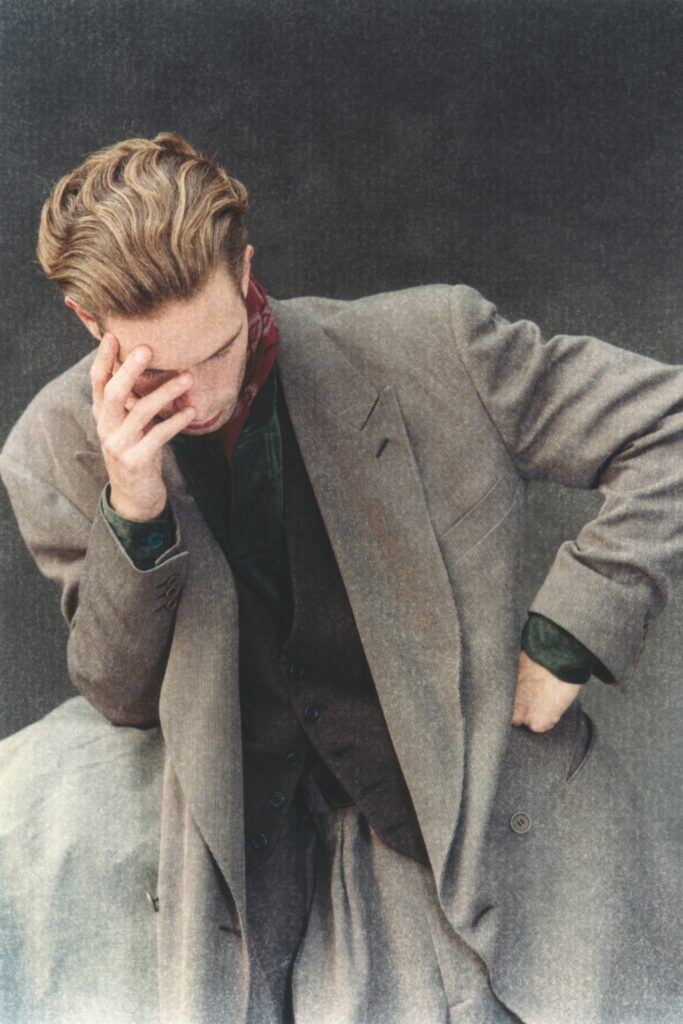

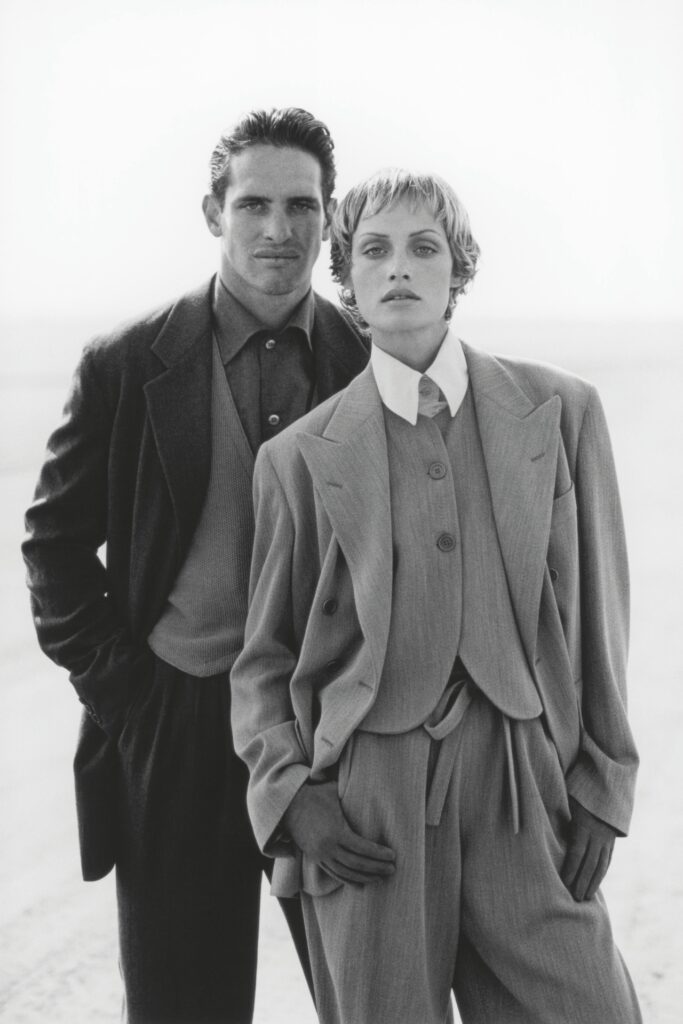

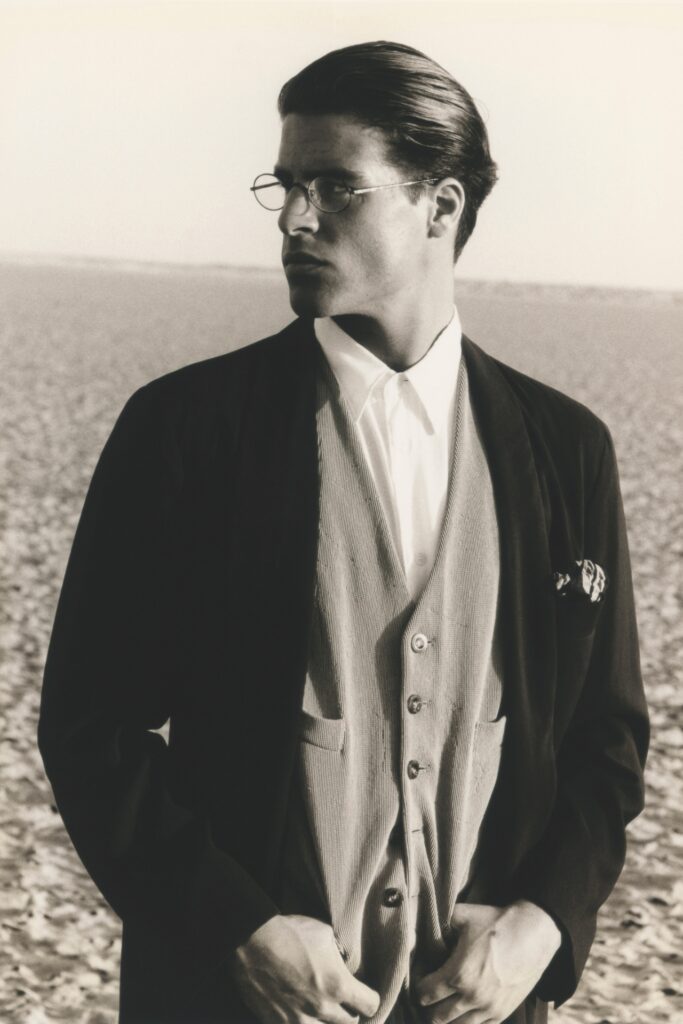

That image, captured by photographer Aldo Fallai, would be hand-painted onto a billboard in Milan’s busy Via Broletto to coincide with Emporio Armani’s spring/summer 1984 collection arriving in stores. Fallai had already been photographing Armani campaigns for almost a decade by that point – a collaboration in which the Florentine photographer helped visualise the intellect of Armani’s clothes in filmic scenes. His most iconic photographs from the ’70s through to the ’90s capture men in these quiet, everyday slices of life, often in a ponderous or sensual state – men who just happen to be wearing Armani.

Black and white was preferred, but even the coloured ones still conveyed the airy translucence of monochrome. Maintaining the simplicity of greyscale throughout his career, Armani is widely credited with establishing black and white photography in fashion campaigns.

“The use of black and white photography in a sea of bright ’80s colour made them timeless and all the more appealing,” says John Potvin, an art history professor at Concordia University in Montreal and owner of the Instagram account @myarmaniarchive. To his 27,000 followers, Potvin shares images from his physical and digital archives of Armani material he’s collected since 1987. A mix of runway shots, campaigns, film stills from Armani’s work as a costume designer and photos of Armani himself, they’re annotated with captions that read like excerpts from essays. Just as he unearths a new image his well-versed audience hasn’t yet seen, Potvin’s account recalls a time when the internet was a place of wide-eyed discovery.

“I was a teenager in the ’80s and dreamt of a more glamorous place,” he says, “Of course, in those fictional images, that place never really existed, but they certainly allowed me to dream.”

AS A CHILD, Armani would dream while sitting in a darkened cinema as the Allied forces flattened his hometown, Piacenza. With the regularity of a churchgoer, the boy would spend most of his Sundays with his family watching the new Golden Age Hollywood releases; the era’s sophisticated comedies offered a light-hearted distraction while growing up in penury post-war Italy. In a way, propagandist-like, the studios at the time were especially attuned to selling American glamour and fantasy. Watching the elegant leading ladies and stoic men in double-breasted suits would come to influence the way his clothes do the talking.

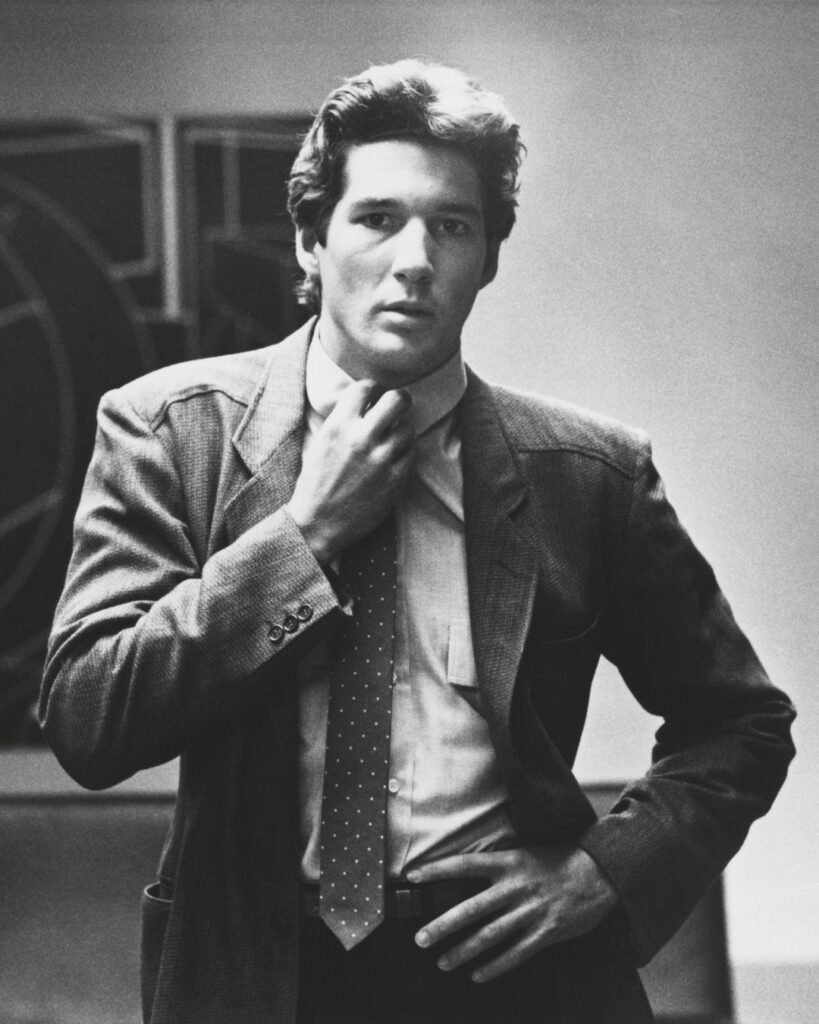

What the films reinforced was the importance of image-making, which inspired his second prolific career, in costume design. And his flair in that realm would enshrine the 1980 thriller American Gigolo in fashion history by making a star of Richard Gere and catapulting Armani into the new gym-obsessed class of corporate America. But his most important film collaborator would be the esteemed director Martin Scorsese, with whom he shared Italian heritage and a mutual admiration.

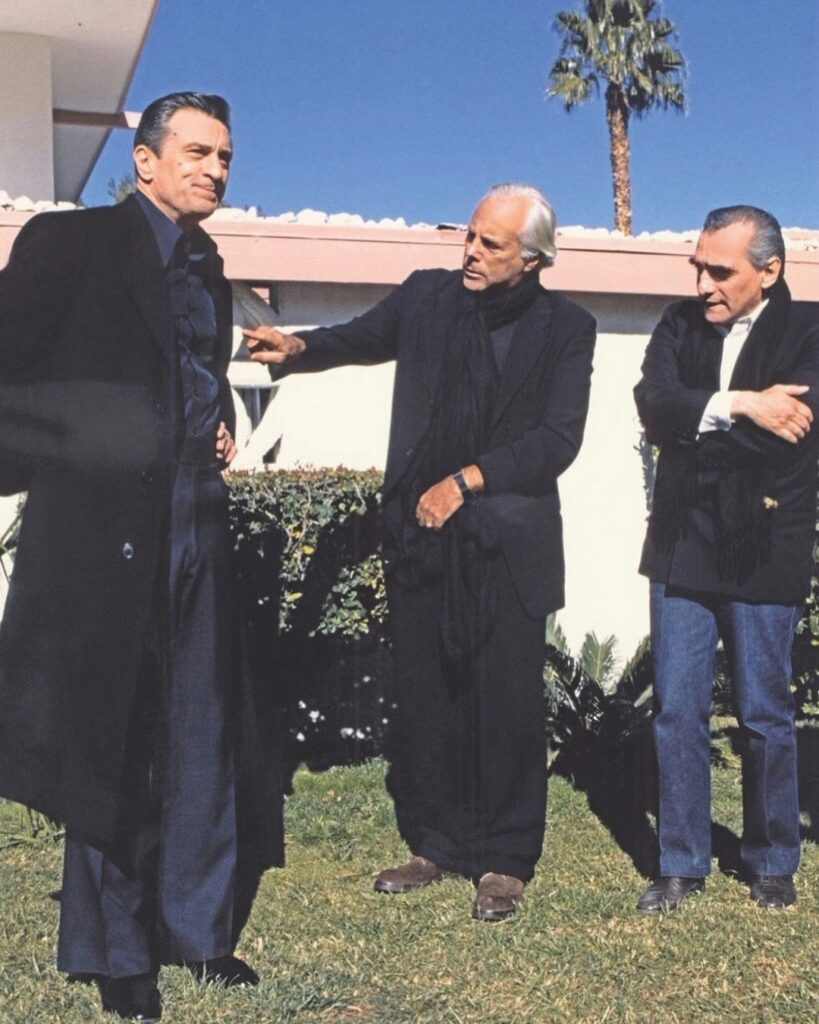

On a clear sunny day on a white-picketed lawn on the set of Casino (1995), Armani is seen pointing to the particulars of Robert De Niro’s inky black coat, with Scorsese standing behind him watching like a student. “What matters is that it’s a nice Armani coat and a sharp Armani jacket,” wrote fashion critic Rachel Tashjian in the A24 book How Directors Dress. “The essence of this fashion designer, this humble king of understatement – for whom understatement isn’t modesty, but glamorous dignity – will add something to the film. It’s like Scorsese is letting Armani direct the clothes.”

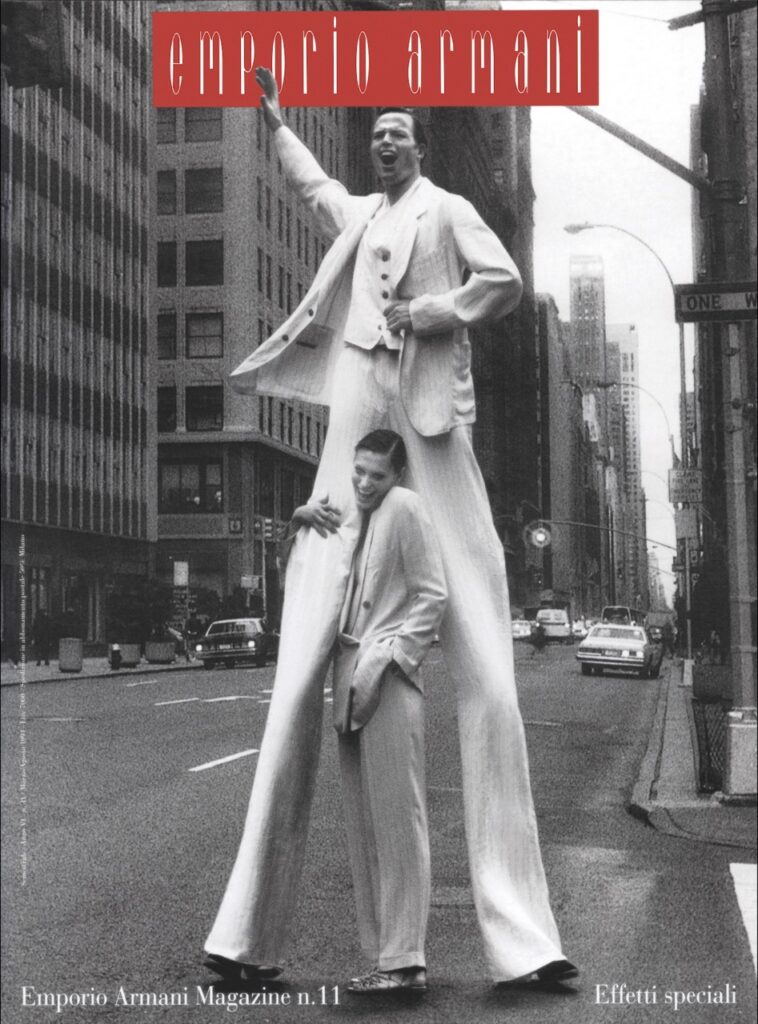

Conversely, Armani granted a similar auteurship to his campaign photographers. On the back of his film career, the ’90s proved to be an important decade for the brand’s global expansion, so his campaigns upped the ante with international shoots to reflect these new markets. One early initiative was the bi-monthly glossy Emporio Armani Magazine, which launched in 1988, equal parts editorial endeavour and cultural bible, with essays written by prominent authors. Armani was the first designer to combine commerce and content in an elite conceptual product.

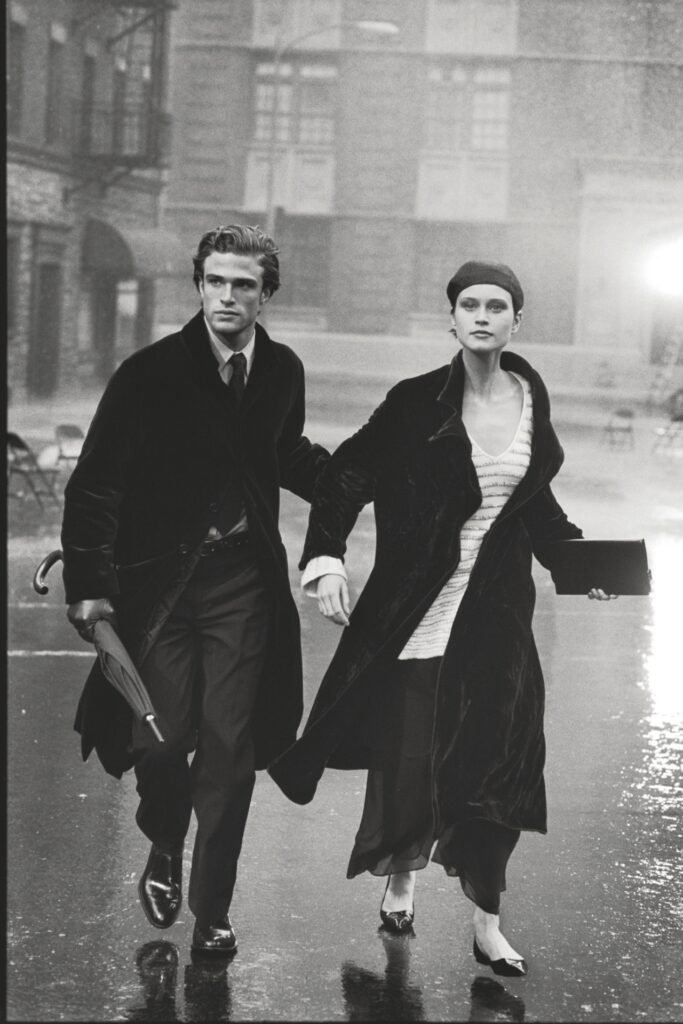

COME 1994, contributing editor Stefano Tonchi was a fan of British photographer Max Vadukul, whose pioneering black and white fashion photography was a no-brainer to pair with Armani’s house style. Vadukul’s first assignment was the March/April cover. “You were chosen as an author, and once they selected you, you were allowed to go about and do what you were supposed to do,” he tells me. “Indeed, one is encouraged to express oneself for a designer like Armani. It’s what they look for.”

Vadukul was living in Paris at the time. “It [was] very simple. I said: ‘I’d like to go to New York to shoot’.” He got to work on a wide Manhattan avenue, where the city’s caricature of waving down a cab reached fantastical heights via Vadukul’s idea to have a male model on stilts, his female companion clutching one of his legs. “They had to make an entire suit from scratch for that [shoot],” he says. “So that was quite a big effort from Armani.” While Vadukul can’t remember if the model was a trained acrobat, even he couldn’t believe he pulled off the shoot. “It was kind of unusual that that worked out.”

Other prominent and emerging photographers of the era were paired with far-flung destinations that intrigued Armani and his knack for world-building: Fallai in Marrakech and Paris; Peter Lindbergh in California. The photographer’s role helped animate the clothes with a sense of worldliness, creating the idea that Armani can exist anywhere, in any climate and culture. When asked about the staying power of the photographs, Vadukul says: “The photographs are good today, they were good yesterday and they’ll be good tomorrow.”

It’s a legacy of timelessness that young designers of today would hope to emulate. Much of Potvin’s audience is comprised of designers, photographers, editors and menswear enthusiasts for whom “these images are an important reminder of how clothing can be done and done well . . . clothing constructed to meet the needs of real people with real bodies,” he says. “Looking back, those images and campaigns reveal a vision of a unique approach to design and image-making.”

Taking a break from writing this story, I went onto my phone and happened upon a menswear content creator giving a tutorial on what to wear on a dreary day. He pulls up his reference: a photograph from the ’90s of a young Kyle MacLachlan – the American actor and David Lynch collaborator – the focal point being his voluminous Armani trench with its belt hastily tied and his hands stuffed in the pockets.

He notes how self-assured the actor appears walking on the footpath, cocooned in the coat’s volume, with his chin turned up to the sky and a cigarette bouncing on his lips. In that moment, the appeal of Armani’s images for a twentysomething today – images that are older than the observer – has become a blueprint for how to dress with confidence and ease. Armani’s clothes represent a compelling form of armour. The sage’s work is done. His students go forth.

A version of this story appears in the September 2025 issue of Esquire Australia with the title “Image Architect”, on sale from September 15.

A correction has been made to reflect the passing of Giorgio Armani on September 4, 2025.

Related:

Giorgio Armani has died, age 91

Giorgio Armani, American Gigolo and the art of red carpet dressing