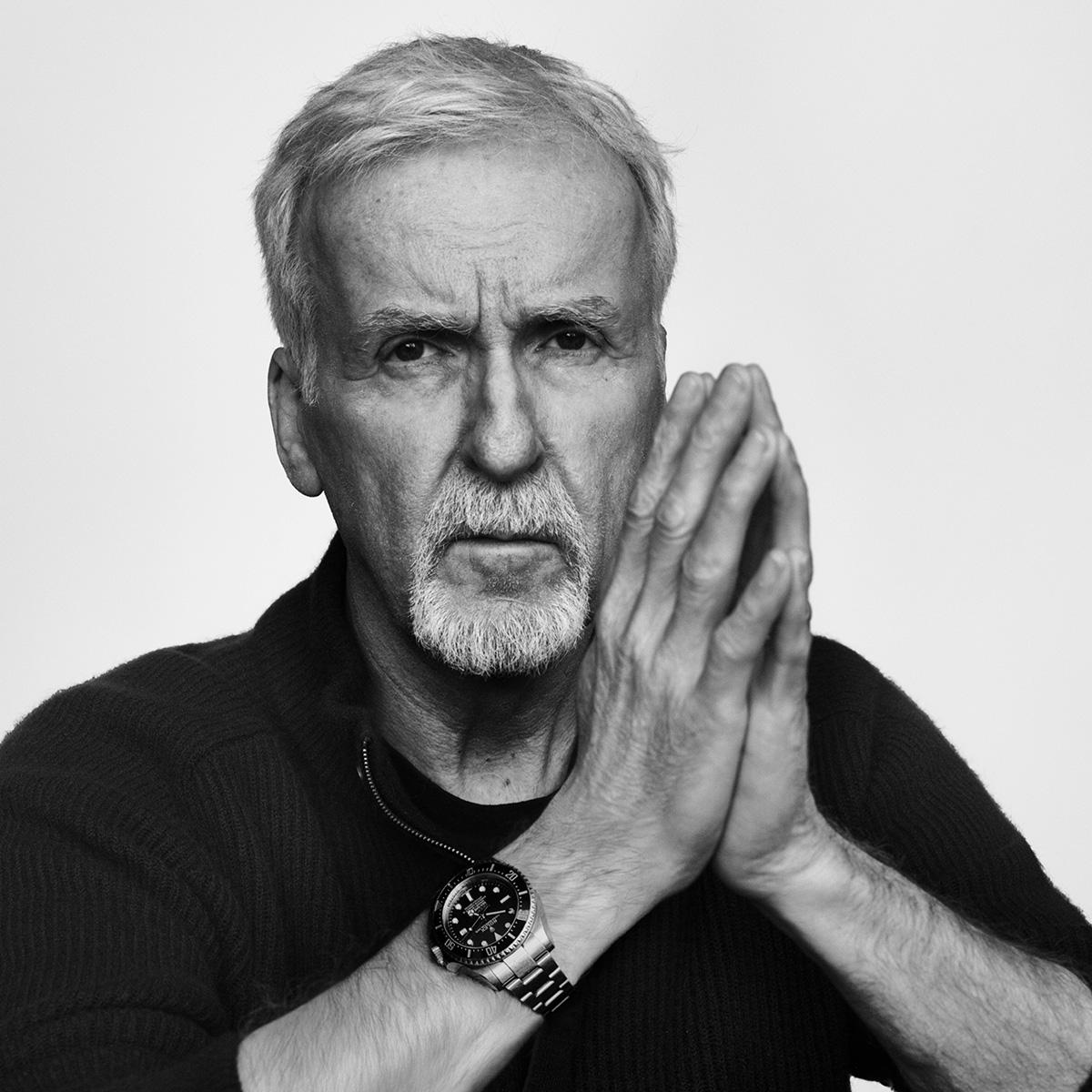

Guillermo del Toro Reimagines ‘Frankenstein’ as a story of fathers, sons and forgiveness

“It’s not about monsters. It’s about what makes us human”

Guillermo del Toro doesn’t make monster movies. He makes films about what it means to be human – about longing, guilt, love, and the impossible hope of redemption. In his long-awaited Frankenstein, he transforms the world’s most famous tale of creation into something raw and intimate: a story of fathers and sons, pain and forgiveness, and the terrible beauty of giving life when you’ve known loss.

Ahead of the film’s release, the Oscar-winning director spoke with Esquire about the lightning-struck casting of Oscar Isaac and Jacob Elordi, the anatomy of his creature, and why Frankenstein became his most personal reckoning yet.

Del Toro has never viewed Frankenstein as horror. At least, not in the traditional sense. “Generically, it can be a horror film, but for me, it was a history of fathers and sons. Like a melodrama of a lineage of cruel fathers and mistreated sons. I wanted it to be a movie about forgiveness,” he says.

Mary Shelley’s novel, he notes, was born from grief. “Her miscarriages, the death of her mother, the itinerary she follows with Percy when they elope,” he says softly, “it’s reflected in the book.” For del Toro, those ghosts were permission to draw on his own. “I wanted it to be very autobiographical for me, in the way that the book is very autobiographical to Mary Shelley. I’ve always considered it a personal film”

The result is less horror than inheritance. A film about the wounds we carry forward, and what it takes to stop repeating them.

Del Toro first read Frankenstein at age 11 and has returned to it obsessively since. “I like the messiest version, the 1818 text,” he says. “I know it so well, I know her life so well, I know the life of the Romantics very well, and I thought, whatever I do to change it, if I feel the spirit is preserved, I’m ok. Because adapting is like marrying a widow. You have to be very respectful of the late husband’s memory, but, you know, now and then, you have to party like it’s 1999.”

That reverence defined his approach and his casting. “I was meeting Oscar Issac for a general meeting,” del Toro says simply. He remembers meeting the actor with no plans to collaborate. “I saw in his eyes brilliance and pain. He was very seductive and very vulnerable. I thought, ‘This is perfect because Victor is highly intelligent but emotionally stupid.’”

Isaac, he explains, embodies contradiction: charisma without empathy, beauty shadowed by guilt. “This is a guy that is capable of seducing an entire room with a speech and a little bit of sway, and yet he could be perfectly wrong. He was never going to be a villain, even if he did despicable acts, you understood he did them from pain.”

Del Toro reframes Victor not as a mad scientist but as a mirror – a man undone by his own creation and incapacity for love.

If Isaac represents intellect and ego, Jacob Elordi is his counterpoint, portraying a figure of innocence, fragility, and emerging awareness. “We prepared,” del Toro recalls. “We talked about how could he play nothing when he’s born? We talked about babies’ developmental stages.” Elordi studied Butoh, the Japanese theatre form known for reanimating the dead, to craft the creature’s movement. “When he came in, he had an innocence the first day of shooting,” del Toro says. “He had a purity of somebody that had never lived, I was absolutely enthralled. And then he started moving. He moved like a baby and an insect and something disjointed.”

“I can tell you this much about Jacob Elordi, he doesn’t need more than two takes. He is absolutely remarkably on the dot every time. He is one of my favourite actors of all time.”

That physical strangeness reflects del Toro’s design philosophy. “Many Frankenstein versions look like accident victims,” he says. “And I thought, well, if a guy has been planning to do this for twenty, thirty years, he’s going to make something beautiful. I needed it to feel like an unborn baby, almost translucent and pale and like a blank.”

The makeup took up to ten hours a day to achieve a being that was both anatomical and divine. “He’s not going to look like a bunch of bodies put together, but actually like a newly minted being, Adam. Mary Shelley calls him Adam in the novel and I needed that – I needed that biblical feeling. He needed to look saintly, messianic, and blank at the same time,” del Toro explains.

For all its grandeur, del Toro’s Frankenstein isn’t a warning about science or technology. In fact, he rejects that idea entirely. “For me, it’s never been a warning about science,” he says. “It’s always been the urgent John Milton question of, ‘What are we? Who are we? What makes us human? And do we exist in God’s plan?’”

He points out that in Shelley’s novel, the creature treasures Paradise Lost, which turns creation itself into a theological riddle. “I’m an ex-Catholic, and the movie is full of Catholic imagery and guilt and parental pain and all that,” del Toro says. “Once a Catholic, always a Catholic.”

That iconography – the wounds, the resurrection, the sacrifice – runs through the film like blood through marble. His God is both loving and cruel; his humans, equally divine and damned. It’s this tension between awe and agony that makes del Toro’s Frankenstein feel alive. The story becomes not one of horror, but of longing. A creator facing his own loneliness, a creation desperate to be seen.

In del Toro’s Frankenstein, horror is not the scream in the dark – it’s the silence that follows. Creation is confession. And resurrection isn’t victory. It’s forgiveness.

Related:

Ranking the best red carpet looks from the ‘Frankenstein’ press tour