LIKE A RISING NUMBER Of Australians, Nik Smith* had made peace with the fact he’d probably never own his own home. Before he moved to Melbourne, the school teacher and musician lived in Sydney for 20 years, shifting between almost as many share-houses during that time. Whenever he managed to save up a decent amount of money, he’d choose to spend it on a trip or some new music gear, because unlike the generations before him, chasing the age-old Australian dream felt so firmly out of reach.

“When I moved from Sydney, I had no intention of buying a house here. I always just saw myself as a renter,” says Smith, who goes by DJ Earl Grey when he’s spinning cerebral dance music at bars around the city. But shortly after moving to Melbourne, the 34-year-old was told about a local organisation that, at its core, was challenging the conventional housing market by building and selling sustainable, architecturally-designed apartments at an affordable price. There was no marketing, no display suites, no real estate agents or commercial developers involved; the organisation known as Nightingale Housing was founded and run by a group of architects, and unlike the conventional auction system, the apartments didn’t go to the highest bidder. To own one, Smith had to enter a ballot.

“I kind of entered the ballot for fun, and I actually got my first preference, which was the top floor overlooking the sunset,” he recalls. “Then I was like, ‘Okay, what will this actually cost? Is it actually possible?’”

The Nightingale sales model required Smith to put down a five per cent deposit, rather than the market average of 20, which made it possible for him to sign on the dotted line. “It was curiosity that pushed me to apply. Being successful in the ballot forced me to take saving really seriously for the first time in my life.”

Though Smith’s DJ moniker is unique, his circumstances aren’t. Australia is currently in the midst of a housing crisis, which is being intensified by cost of living pressures, rising interest rates that are prompting mortgages to rise and rents to skyrocket, a housing supply shortage and a cultural mentality wherein housing is viewed as an asset that’s designed to be bought and sold. Over the years, this has resulted in some people owning more houses than they can live in, while others are priced out of the market completely.

And few people are being left unscathed. A September 2023 report by KPMG Economics revealed that house prices will rise nationally by 4.9 per cent over the next nine months before surging by 9.4 per cent in the year to June 2025. Meanwhile, the outlook is similarly grim for renters. While writing this story, an Apple News notification popped up on my phone: ‘Rental affordability goes from bad to worse’, it read.

According to the Reserve Bank of Australia, advertised rents across the country are currently 30 per cent higher than pre-pandemic levels, while in October, the national rental vacancy rate hit a new record low of 1.02 per cent. As of November 2023, the national median weekly price of all rentals on realestate.com.au is $550, up 14.6 per cent on the previous year.

The federal government knows it has a big, urgent problem on its hands—in 2023, the prime minister committed to funding the building of 1.2 million new ‘well located’ homes across Australia throughout the next five years, as part of Labor’s $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund. The Greens don’t think this goes far enough; they have called on the Albanese government to offer states incentives to freeze rent increases over the next two years, while pushing them to spend a minimum of $5 billion extra per annum on public and ‘genuinely affordable’ housing.

But this story isn’t necessarily about the extent of the issue—there are plenty of places you can go to for news about that. Instead, this story is about a very real solution to housing accessibility in this country. It began with a small group of Melbourne-based architects frustrated by the status quo, before it spread into a national movement that isn’t just providing people like Smith with a home to own—it’s setting a new precedent for the government and housing developers to do better in the process.

A generational shift

“I think the expectation that ‘My parents had a house with a backyard, so I’ll have a house with a backyard’… it doesn’t really work like that anymore,” says Dan McKenna, the CEO of Nightingale Housing. “But for a lot of people, the alternative to that was typically these really low quality, poorly built apartment buildings, which weren’t necessarily somewhere you could live long term and actually build a healthy life.”

McKenna began his career in architecture soon after graduating from university, and, similar to Smith, was moving from rental to rental with home ownership a distant speck on the horizon. Unlike people of his parents’ vintage, who purchased property in the ’80s and ’90s before the financial deregulation of housing finance interest rates in Australia put the cost of home loans in the hands of the market (which, over time, has contributed to house price inflation and a widening of the deposit gap while wages have remained stagnant), for McKenna (and millennials of his vintage), the barrier to entry was much, much higher.

Back then, buying a home in a desirable area was considered one of the safest investments you could make. For many young people today, it’s a recipe for debt (following the November 7 2023 interest rate hike, data collected by consumer research organisation Finder found that in Sydney, an average household income of $261,773 is needed to afford the average priced house; in Melbourne it’s $171,235, while Darwin remains the most affordable at $116,125). Despite this, the very Australian attitude that owning a home with a backyard and white picket fence equals security and success persists, because it’s been passed down and inherited by 30-year-olds just like me.

And while in many European countries, people live happily in apartments for their entire lives, we’ve been conditioned to view apartments—which, by virtue of their size and density, have a far lower carbon footprint than houses—as something of a temporary stepping stone. “In Scandinavia, for example, generations of people are raised in apartments,” observes McKenna. “But then you come to Australia and it’s like, ‘No, apartment living is only for this stage in your life’, and so you don’t end up staying in one spot for long at all.”

But the goal posts are beginning to shift. “People are starting to understand that overstretching themselves to have a certain asset which may or may not make their life harder isn’t necessarily a path that’s feasible, or something that people even really want to commit to,” says McKenna. “We value slightly different things. I think a connection to place, and being able to live a healthy, more sustainable lifestyle is really front of mind for a lot of people. Ten years ago, sustainability was still considered this fringe thing, and now it’s front and centre for everybody. People are thinking more about how they get around the city, what kind of electricity they use… and I think Nightingale presents an opportunity for people to live in a more sustainable way.”

Rethinking the model

McKenna was working as an architect at Breathe Architecture, the award-winning Melbourne studio behind avant-garde projects like Sydney’s Paramount House Hotel, when the firm’s founder and design director Jeremy McLeod was developing what eventually became Nightingale. Following the successful completion of The Commons, a medium-density, multi- residential prototype in the north Melbourne suburb of Brunswick, Breathe launched its Nightingale initiative in 2016 with the tagline: Homes built for people, not profit.

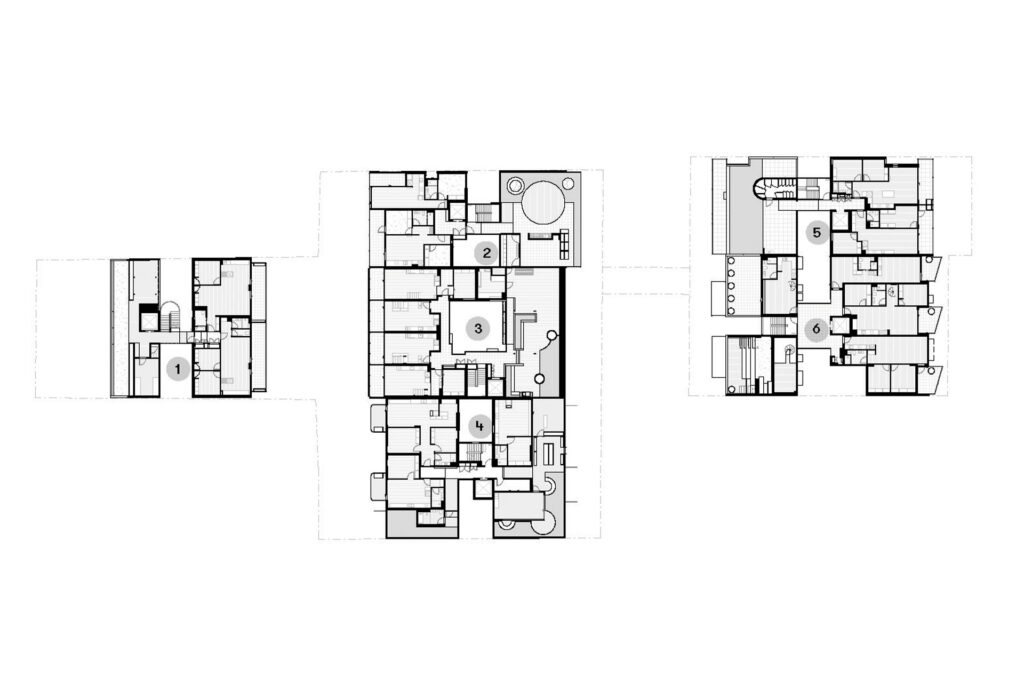

The premise was relatively simple, yet radical given the context in which it was hatched. A not-for-profit organisation, Nightingale would design, build and sell socially, financially and environmentally sustainable housing that’s built to last. It would achieve this through a number of measures, some of the most fundamental being: removing the need for car parks (and cars) by building in areas that are well connected by public transport; adopting a ‘design of reductionism’ approach, whereby unnecessary features like false ceilings are done away with to save on materials and therefore money; removing the need for individual laundries by building a communal one on the rooftop, which gives owners more square meterage inside while encouraging a more communal environment. Nightingale buildings are also gas-free, which reduces its occupants’ greenhouse gas emissions but also eliminates a utility bill.

“We’re really transparent about the decisions we make and why we make them,” explains McKenna. “And when you put the numbers against it and sort of say, ‘We could give you a laundry, but your costs are going to go up by this much’, with the cost of everything right now, we find most people are pretty happy to do their laundry on the roof if it means saving money.” It’s worth pointing out that McKenna isn’t just preaching—he’s practising. He lives in a Nightingale building along with his partner and children. “I actually like the fact I don’t have to sit on my couch and look at a clotheshorse with my socks and undies drying,” he acknowledges with a laugh.

Just like Nik Smith—and every other person who wants to own and live in a Nightingale apartment—McKenna had to enter the ballot. It’s this sales model that makes Nightingale so unique, and so accessible. The price of an apartment is the same for everyone (a one-bedroom Nightingale apartment starts at around $470,000), but chance decides who gets to own it.

“It’s a weird way to sell homes, especially when historically in this country, homes go to whoever can pay the most,” observes McKenna. “But Nightingale was a big reaction to that and a ballot was the fairest way we could think to do it—to have the process play out in a way that’s literally chance.” Anyone can enter the ballot, and whether you earn above or below the average Australian salary (which, according to ABS figures, was $92,030 before tax as of August 2023), you have the same chance of getting the apartment.

“We literally put people’s names in a hard hat. It takes us about an hour to pull out names and then we’ll call people one by one and let them know if they’ve been successful or not.”

More recently, Nightingale implemented a ‘priority ballot’, whereby key groups in most urgent need of housing—Indigenous Australians, people living with disability, single women over 55 and ‘key community contributors’ like nurses, and teachers—were given a “double dip” in the ballot, with 20 per cent of the units in a building set aside for people in these groups. Still, demand is dramatically exceeding supply, and it’s not uncommon for prospective buyers to enter the ballot a handful of times.

“We would love equilibrium—that there was a house ready for everybody who signed up through our website,” says McKenna. “But we’re a reasonably small company and we’re aiming big. What we see as success is changing the mindset in the marketplace— getting much bigger companies looking at us and going, ‘Okay, why is this working? Why is this really popular? The bigger impact we have across the country, the better.”

More ways to own (and rent)

With such a disruptive model—and an open- source mentality—it hasn’t taken long for Nightingale’s idea of success to become a reality. In 2020, Australia’s leading superannuation fund AustralianSuper became a shareholder of Assemble, a property developer that exists to provide fairer, more financially accessible, better-designed homes in Australia. Like Nightingale, Assemble was established by an architecture firm back in 2010. According to Emma Telfer, the chief operating officer of Assemble, the original aim was to “lift the design standards within multi-residential, medium density apartment living in our inner cities.”

When AustralianSuper became a backer, Assemble transformed into a business with the ability to build affordable, well-designed housing at scale (the superannuation company’s interest was two-fold; in addition to generating stable returns for their members, working with Assemble also chimes with its social impact agenda).

Assemble’s first project, in the Melbourne neighbourhood of Clifton Hill, was completed in 2016. Since then, Assemble has finished its pilot build-to-rent-to-own project in Kensington, and is currently building two more Melbourne projects due for completion in 2024.

Assemble Futures and Nightingale share a great deal in common—including the desire to make good housing accessible to more Australians. But where Nightingale apartments have traditionally been owned by their occupiers, Assemble operates a unique ‘built-to-rent-to-own’ model. When someone signs a lease on an Assemble apartment, the rental price is set for five years, eliminating any shock increases. Every tenant is also given the option to purchase their apartment, again, at a fixed price agreed upon at the commencement of their five-year lease. At the end of those five years, or sooner if they prefer, the tenant can choose whether to exercise that option and become the owner of their apartment or go on their merry way, no financial penalty involved.

“It’s up to five years of renting at a pre-agreed price, which gives people more time and stability to save for a home deposit – if they decide they do want to purchase,” Telfer explains. “We also have a financial coaching program that’s opt-in and free of charge. It’s very much about your relationship with money and what’s required to achieve your financial goal, so you feel confident developing a household budget, putting a savings plan together and staying on track.” The rent Assemble residents pay throughout their five- year tenancy doesn’t go towards the purchase price of the apartment. But by being pre- agreed, saving becomes much easier than it would in the standard rental market of today.

“For a number of our residents, the idea of home ownership has been so out of reach that they haven’t even considered it’s possible, so they haven’t done the work to get themselves into a position of financial readiness,” says Telfer. “A lot of people feel like the mountain is just too steep.”

Assemble’s 362-apartment project at 402 Macaulay Road in Kensington is a little different, though. It’s a ‘build-to-rent’ initiative, which refers to a residential development where all properties are owned and managed by a single entity. This differs from the ‘build-to-sell’ model that’s most common in Australia, where a developer sells each individual unit to owners, who then manage the property and, should they become landlords (now called rental providers), increase the rent as they please. Build-to-rent projects are popular in Europe, Telfer explains; the idea is that by making the homes desirable and accessible to the rental demographic, tenants will stay for longer periods of time. “It’s quite unique for Australia,” says Telfer, noting that the project will feature a diverse range of rental homes urgently needed in the current system, including a percentage of social housing, delivered in partnership with community housing provider Housing Choices Australia

As you read this, Nightingale is putting the finishing touches on its first build-to-rent project, which also happens to be its very first Sydney project. While there are Nightingale buildings in Adelaide and Perth, the organisation was previously unable to branch into Sydney due to exorbitant land prices, and it wasn’t until Fresh Hope Communities, a religious organisation, offered its unused land to Nightingale that the not-for-profit could bring its model of affordable housing to the city. The development is located in Marrickville, close to the train station, as well as bars and restaurants that make the neighbourhood such a desirable part of the inner west.

“Fresh Hope has retained the land, so they are the landlord offering people long-term leases at affordable rates deep into the future,” explains McKenna. “It was only through collaboration with landowners like [Fresh Hope] who are like-minded that we could get things like that happening in Sydney.” Rent is determined by government legislation around what is classified as an affordable rental in the area, says McKenna, adding that rent for a unit in Nightingale Marrickville “will have a three in front of it,” meaning it will land in the $300- $400 bracket, which, as per those realestate.com.au statistics, is roughly $200 less than the median weekly price of all Australian rentals.

Architecture for everyone

When researching this story, I was also surprised to learn that architects only work on three per cent of housing in Australia. The remaining 97 per cent of homes are built by big property developers and commercial home construction companies like Metricon, which offer more affordable, off-the-plan options and tend to be more popular in regional and outer suburban areas. In Australia, engaging an architect to design your home is expensive, hence the perception that architecturally-designed homes are only available to the wealthy. But Assemble Futures and Nightingale don’t believe this should be the case.

“I think there’s a huge role for the architects to play in the housing crisis,” comments McKenna. “Architects are trained in questioning things and challenging things and coming up with really novel solutions.”

Nightingale’s approach to design is “one of reductionism,” says McLeod, the co-founder and design director of Breathe. “In Australia, you often see things that are really over-designed. But by reducing the number of materials we use, the apartments feel pared back, minimal, honest and elegant.” Foregoing a false ceiling might reveal exposed pipes, but it also creates the feeling of a loftier, airier space.

Inadvertently, from this approach Nightingale has pioneered a new design aesthetic; don’t be surprised when you begin to see industrial-style exposed pipes feature in high-end interior design magazines.

The apartments in its Marrickville complex, the ones renting for between $300-$400 per week, are uniquely designed too; named ‘Teilhaus’, the German word for ‘part of house’, they are small footprint, space-efficient homes that maintain functionality through joinery and flexible spaces, such as a bed that can be neatly concealed by a curtain when guests come around. (A portion of Nightingale’s owner-occupier buildings include Teilhaus apartments, which start at around $300, 000.)

“Tielhaus apartments are 25 square metres. We’ve found people in Australia are really unwilling to engage in a conversation about size, and when we’ve got the climate crisis and housing crisis happening, size really does matter,” says McLeod. “We have the biggest housing in the world in Australia—bigger than the US and Canada. If we build smaller housing, it means we might have half our embodied carbon, half our operational carbon, half our utility bills, half our price point to buy in, half our mortgage repayments… it seems like a no-brainer, and the architecture can still be beautiful.”

While Breathe was behind the design of Nightingale’s first projects, in 2021, Nightingale became its own, separate entity—though it still shares close ties with its mothership. “Breathe is the band, Nightingale is the studio album,” explains McLeod. Today, a range of award-winning architects design the buildings, from Melbourne studio Kennedy Nolan to Sydney firm SJB, which recently wiped the floor at the National Architecture Awards, claiming three awards (including the coveted Robin Boyd Award for residential design) for a small footprint home in Surry Hills, Sydney.

Green spaces are also key to both Nightingale and Assemble. “We embed as much green space and landscaping in and around the building to really bring it to life,” says Telfer. “We’ve put a lot of emphasis into community-engagement when it comes to design, and a lot of the features embedded in our projects are designed to foster community connection. Like the dog wash area. We’re very pet friendly. In our pilot project, which is 73 apartments, I think we have over 50 dogs.”

While Assemble’s design is guided by its sustainability mandate, the layout of its buildings is also created to encourage more incidental community interaction. Communal spaces like ‘workshops’, which act as a garage-style space for residents to create and tinker, are a defining aspect of Assemble’s communities. It’s quite literally designed to prevent loneliness. “You can really live a full life in one of our buildings.”

Hope after all

Smith has lived at Nightingale Anstey in Brunswick for four years now, and he doesn’t have any plans to sell up and move out. “I’m really happy there and really comfortable. It feels like there’s a lot going on in the area; new places are popping up everywhere and it definitely feels like somewhere I’d like to live for a long time.”

He recently started a bulk-buying coffee club, and says someone else in the building organises a bulk dishwashing powder order, while it’s not uncommon for families with kids, retirees and young professionals to find themselves sharing a drink on the rooftop.

With hundreds of homes in the planning stages, Nightingale currently has 254 homes under construction, while Assemble plans to complete its build-to- rent project by late 2025. These trendsetters have also set the precedent for other organisations to develop and finesse similar models—Milieu is another Melbourne-based company specialising in progressive, sustainable residences. In 2021, it became B Corp certified. As the cost of living crisis intensifies, the work these organisations are doing is only gaining momentum. Perhaps one day soon, the alternative pathways they’ve pioneered will become the new norm.

Smith is convinced. ”If owning an apartment, being part of a community, living more sustainably and not having a car is important to you, it’s probably the best, most well-designed option there is.”

This story originally appeared in the December/January 2023/24 issue of Esquire Australia. Subscribe here.