The psychology of cheating in sports

Despite harsh penalties and increased vigilance from authorities, cheating in professional sport remains rampant. But what drives an athlete to break the rules? And if it’s human nature to seek advantage, can cheating ever be stopped?

WHEN MATT SHIRVINGTON looked down his lane from the starting blocks at various points in his sprint career, he knew quite a bit about his fellow competitors. He knew that they, like he, had trained their whole lives for this moment. He knew they and their families had made sacrifices that outsiders would find difficult to fathom. And he knew plenty about the lengths to which his rivals had gone – from their finely calibrated nutritional intake to their lactate-chasing cold-water plunges to their pinpoint visualisation sessions with crack sports psychologists – to propel them down the track that little bit faster.

What Shirvington didn’t know – though he had his suspicions – was who among those lined up either side of him had sought an extra, illegal advantage. In other words, he didn’t know who had cheated.

“I trained and competed against guys that did [cheat], that got caught,” says Shirvington, who finished fifth in a semi-final of the 100m at the Sydney Olympics and previously held the Australian record with a time of 10.03 seconds. “My old coach was Linford Christie and he got caught at one point [in 1999, when he tested positive for the steroid nandrolone], so I have been adjacent to it happening in the sport. And obviously the 100-metre sprint is one of the most renowned for drug cheats, along with cycling and a few others. But I never did and never really had any ambition to [use performance-enhancing drugs].”

Why not, you might ask, if it was clear that his competitors were doing it? Shirvington’s response betrays the nuance and self-awareness of someone who’s given the issue due thought. “I always had the attitude that I’d had a pretty blessed upbringing in Australia, on the Northern Beaches [of Sydney], and athletics was an opportunity that I grabbed with both hands and loved doing,” he says. “But at no point did I see the value in sacrificing the rest of my life or ambitions after retirement to go and ruin it. One, by putting something in my body that I didn’t fully understand the outcomes of. And two, the reputational damage. I mean, why would I want to cheat when that’s not the character that I am? That’s not the person that I am?”

‘Character’ is a key word in any discussion about cheating in sports – or other domains, for that matter. Because while circumstances, such as poverty and desperation, will always be part of the equation, psychological factors are the metaphorical starter’s gun – perhaps even the smoking gun – in an athlete’s decision to break the rules.

“The biggest thing that would motivate someone to cheat is inadequacy,” argues Shirvington. “Someone that has shown some potential but hasn’t quite got the ability to really push past mediocrity and then get to a really elite level.”

While Shirvington’s argument rings true, often more sinister behavioural traits are at play. Narcissism, Machiavellianism and even psychopathy have all been found to contribute to cheating in sports. And these same traits also appear to be more common in elite athletes. In some cases, you could argue, they are integral to athletes’ success.

It’s reasonable to believe that it’s human nature – or perhaps just nature – to cheat. “The way to think about cheating is that deception is common throughout the animal kingdom,” says Bill von Hippel, an evolutionary psychologist and author of The Social Leap: The New Evolutionary Science of Who We Are, Where We Come From, and What Makes Us Happy (2018). “Animals that camouflage themselves as something else, that’s deception. Evolution works by any means necessary. It’s an amoral process. So, anything I can do that would give me a leg up, I’ll do.”

In this context, you can see why sport, a confected battle governed by strict, though frequently changing, rules and one offering outsized financial and personal rewards, is particularly vulnerable to cheating. A 2011 WADA-commissioned study found 44 per cent of elite athletes are doping, a subset of cheating. In recent years, we’ve seen our cricketers illegally rub sandpaper on the ball to assist swing bowling; Russian and Chinese swimmers continue to be involved in serial doping scandals; cycling, of course, has seen its biggest star, Lance Armstrong – along with numerous others – stripped of titles. Even sports as disparate as chess and fly-fishing have been rocked by cheating scandals. In the case of the latter, in 2022, fly-fishing teammates Jacob Runyan and Chase Cominsky stuffed their catches with lead weights and fish fillets at an Ohio fishing tournament; they were later handed short jail sentences.

While you could argue that technology is increasing opportunities to cheat, the truth is, cheating and sport share a long history. As Mike Rowbottom, author of Foul Play: The Dark Arts of Cheating in Sport (2012), told The Guardian in 2015: “It [cheating] has been the case since the ancient Greek Olympics and it is still the case now. If anybody thinks this is a mountain, and we’ve reached the top and can sort it all out now, think again. Cheating in sport is not linear. It’s cyclical.”

It might also be inevitable. Indeed, you begin to wonder: is sport merely a distillation of the age-old battle between behavioural instinct and civilised norms? And by attempting to clamp down on cheating, are we fighting a battle – or just playing a game – against ourselves?

TWO MEN WALK into a bar. There’s no sport on TV to distract them, so they do what men have long done in bars: they challenge each other to a fight. They are of similar build. There is no way to discern who will prevail. So, what do they do? They attempt to intimidate each other by signalling dominance.

“Whenever two members of the same species come into conflict, all they want to know is who would win,” says von Hippel. “They don’t want to actually engage in conflict; they want to resolve. And what that means is, now there’s room for lying and cheating, because if I can convince you that I would win if we came into conflict, well, now I might be able to get you to back off.”

Von Hippel, an Alaskan who for a time was a professor of psychology at the University of Queensland, says the same signalling occurs in combat sports. “You look at every one of those boxing matches and they’re right in each other’s face, trying to get the other one to back down. And you look at [the All Blacks] doing the haka. It’s a testosterone-raising, intimidating event that’s designed to make the other side go, Uh-oh. None of those things is an example of cheating, but they are examples of posturing where you could introduce the possibility of cheating.”

If deception is an evolutionary trait, its prevalence means that suspicion is likewise ubiquitous, says von Hippel. “All humans lie and cheat. [But] society doesn’t like it when you do that, so how do you curtail it? Everybody wants to get away with it, but they don’t want others to get away with it. It’s kind of a complicated battle.”

Society, of course, is an ostensibly civilised social structure in which rules govern behaviour and penalties are issued for infringements. These include suspensions and fines, as well as social penalties such as shame and isolation. That dynamic means that those who cheat will often seek to rationalise their behaviour, says von Hippel, who in a study published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin found 50 per cent of people would cheat on a test if they thought they could get away with it.

In sports, a similar dynamic exists and athletes, too, will seek to rationalise their actions. The most common justification, particularly in the case of athletics and cycling (not so much in fly-fishing) is: Everybody else was doing it – I had no choice. In some cases, say cycling circa 2005, that may be true. But is it morally justifiable? Well . . . possibly.

The stakes for athletes competing in events or tournaments varies according to their background, a point Shirvington acknowledges. “When you look at some of the athletes that have been caught in the past, they come from very humble upbringings and, in some cases, from small African villages where, quite literally, the money they earn by competing in elite sport allows them and their family to escape poverty,” says the 44-year-old, who now works in breakfast TV. “That’s a pretty big motivator.” This isn’t mere conjecture on Shirvington’s part. While Kenya is getting wealthier, it is still classed as a developing economy in which, as recently as 2006, 47 per cent of citizens lived below the national poverty line. According to a 2023 report in The New York Times, nearly 300 Kenyan athletes have received punishments for doping offences since 2015.

This idea of a link between economic disadvantage and a preparedness to cheat is echoed by Philip Hurst, a senior lecturer in sport and exercise psychology at Canterbury Christ Church University in the UK and a former national distance runner. “I think you go to people in really low socioeconomic countries, where if they’re able to get EPO, win a road race in Europe and get $10,000, that sets them up for life,” says Hurst. “You say, ‘Well I can dope and provide for my family. Why not?’”

According to Damon Young, a Hobart-based philosopher and author of How to Think About Exercise (2014), the temptation to cheat if you’re an elite athlete would be strong. “If people are going to get the prize, the money, the sponsorship, the free flights, the free clothes, the fame, the adoration, if they just win, well, they’re going to try to win,” posits Young, who when he’s not engaging in philosophical sparring sessions likes to jab and prod as a historical fencer. “I don’t think we should be surprised when people are incentivised by incentives to cheat.”

Rationalisations, justified or not, also help allay feelings of guilt in what’s known as ‘moral disengagement’. “It’s the excuses you make to feel better,” says Hurst, who cites the extreme example of Nazi Germany, where officers ordered soldiers to kill innocent people. “The soldiers would say, ‘I was told to do it by someone else’,” says Hurst, who says this justification is known as ‘displacement of responsibility’. There are eight other justifications used in moral disengagement, he adds, including diffusion of responsibility (everyone else is doing it) and what’s called ‘euphemistic labelling’ (much like the way we call cow meat ‘beef’ to reduce the association with a living animal, sporting teams will often call performance-enhancing drugs, or PEDs, something else). “You don’t call it steroids, you call it ‘juice’,” says Hurst. “Tyler Hamilton, the cyclist, would call it a ‘red egg’; it wasn’t testosterone.”)

BEHIND HURST ON the wall of his home office is a photograph of former Newcastle United footballer Faustino Asprilla, as well as the researcher’s distance-running hero, Steve Prefontaine. Hurst himself competed for Great Britain in the 3000m at the European Athletics Indoor championships in 2015, before “family life and a PhD got in the way”.

As an athlete who didn’t quite reach the loftiest heights, Hurst says he was never a first-hand witness to cheating or doping. But he could see the signs. “I only dipped my toe into that elite pool, and I started to notice terminology being used, more from a performance-enhancement perspective, of every little thing that you need to do.”

In hindsight, Hurst says, the ethos was “unnerving”, particularly as he would go on to study how athletes can progress from using essentially benign performance aids to PEDs. “If I get encouraged to use a Lucozade or a Gatorade today, what am I going to be doing next month? Does that then lead to me using caffeine, and then does that lead to me to something stronger?”

Cheating could often be the last step in such a progression, Hurst adds, citing Sandpapergate and Deflategate [a 2014 NFL scandal involving the New England Patriots and the deliberate under-inflation of footballs) as examples. “You might start off with little cheats. You get away with it and think, I got away with that. So maybe that progressive nature leads to this false sense of security and then they end up cheating.”

Once you cross the threshold, Hurst says, cheating can then become a slippery slope because the athlete’s moral identity has been compromised. “There’s a bit of a realisation there and they think, Oh, actually, I cheated. Being honest and being fair isn’t necessarily that important to me [after all].”

But what happens when an athlete gets caught? How do they feel then? The answer is usually regretful, says Hurst, who ran a study a few years ago in which participants were offered the chance to improve their sprint times by three per cent. The study, published in the International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, found 70 per cent of those who finished in the top 10 cheated. Not surprisingly, those who were revealed to have cheated said they regretted it. What Hurst didn’t expect was that participants who didn’t opt to improve their time regretted not cheating.

He draws a comparison with Tour de France cyclists. “If you’re competing against people like Lance Armstrong, you’d imagine after a long time you’d think, Well, he’s getting away with this, and that might encourage regret, which then encourages cheating.”

Central to the decision of whether to cheat, of course, are values. Athletes that prize winning above all else are more likely to have a whatever-it-takes attitude, says Hurst. If you have a coach with the same mentality or teammates with eyes fixed solely on the prize, the likelihood of cheating increases.

If, on the other hand, the team or individual values sportsmanship and fair play – principles the Australian cricket team, for example, prioritised in the aftermath of Sandpapergate – then you are likely to pursue these, possibly with zealotry.

There’s just one problem: either by nature or consequence, elite-level competition doesn’t always attract personalities of unimpeachable moral character.

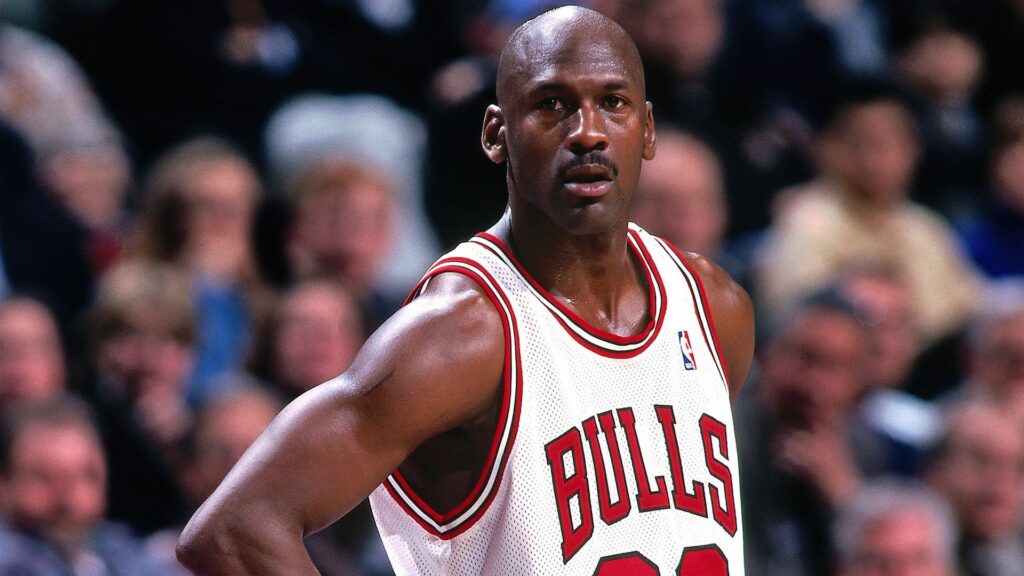

THERE’S A SCENE in The Last Dance where Michael Jordan is inverting his fingers at his own eyeballs, then pointing them at a teammate, as if to say, I’m watching you. Jordan was notoriously tough on teammates, his often-maniacal level of competitiveness causing him to bully them into playing better. In the docuseries, Jordan becomes tearful when recollecting the lengths to which he’d go to get the best out of his teammates. Yet he remains unrepentant: “It is who I am. That was how I played the game. That was my mentality.”

Jordan’s ethos would rub off on his heir apparent, Kobe Bryant, who took the competitive mindset a step further with his infamous ‘Mamba Mentality’, where Bryant was the anti-hero in his own cutthroat universe. Both players were venerated as cold-blooded killers on the court, and I can’t help thinking about their shared legacy as I chat to Adam Nicholls, a professor of psychology at the University of Hull, about his work on cheating in sport and the ‘Dark Triad’ personality traits: Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy.

In a study published in the European Journal of Sport Science, Nicholls and his team found that all the Dark Triad traits were associated with cheating and certain attitudes towards doping among athletes. In respect to doping, psychopathy was found to be a stronger predictor than either narcissism or Machiavellianism, while in terms of cheating, it was narcissism that was the key predictor.

“What we concluded is that psychopaths find it difficult to resist cheating, even though they may get caught, because of the rewards that they can get,” says Nicholls. “Also, they don’t feel any guilt from doing it.”

The interesting thing about these findings is this trio of traits appears to be more common among elite athletes than the general population. In another study published in Psychology of Sport and Exercise in 2019, Nicholls assessed the Dark Triad scores of 1258 athletes, finding elite athletes scored higher on all three traits than amateur athletes. Indeed, you could argue that in the cases of truly transcendent athletes – Jordan, Kobe, Maradona (his 1986 ‘Hand-of-God’ World Cup goal was arguably an act of Machiavellianism) – they’re traits that, rather than besmirching their legacies, are integral to them. Basically, the shit worked.

Nicholls wasn’t surprised by his findings. He believes high levels of Dark Triad traits are likely to be key drivers of the competitiveness and obsessiveness often required to win at the top. “If you look at Machiavellianism, a characteristic associated with that is being strategic,” says Nicholls. “If you’re an Olympic athlete, you’re thinking four years ahead, so you do have to be calculating.” Similarly, he says, if you’re going to be competing in front of 80,000 people, you’ve got to have an inflated view of yourself. And, in the case of contact sports, it helps if you can inflict pain upon opponents without being unduly troubled by empathy. “A lot of these traits do help athletes be successful,” he confirms. “Not just athletes, but people in many walks of life.”

Athletes who possess Dark Triad traits may be tempted to cheat, Nicholls says, because they feel they deserve to be rewarded for their efforts. “What I see is that they have this self-entitlement that they deserve these rewards, they deserve the wins, because of the amount of work they’ve put in,” he says.

But while the Dark Triad traits might be a predictor of which athletes are most likely to cheat, the fact is there are some among the elite cohort who are more vulnerable than others. Your Jordans and Kobes, for example, may not be inclined to cheat because they are already enjoying massive success. Athletes at the very top also have more to lose in terms of reputation and status. It’s those who are on the cusp of the elite level, where their status doesn’t match their self-image, who are perhaps most vulnerable, argues Nicholls.

Hurst agrees that athletes are vulnerable at certain points in their career trajectory. “There are tipping points in an athlete’s career, whether that’s when you’re in the under-18 team trying to make it into the first team, or you’re an athlete that’s been injured and you’re trying to get back to competition. There are certain stages in an athlete’s career where they go, ‘This is something we can do’.”

IF WE ACCEPT that cheating is endemic to professional sport and possibly always will be, what are the options available to sports administrators, legislators, sponsors and we, the paying public? Do we stick with the status quo, in which we assume many or even most competitors are using a variety of performance aids, some of which might be illegal? You could argue, given the colossal success and profitability of pro sport and the enormity of the Olympic Games, that this approach, while certainly flawed, is a largely successful one.

In the case of doping, it’s worth noting that in an era in which athletes are treated as commodities or, conversely, are CEOs of their own personal brands, the imperative to take PEDs isn’t driven solely by the pursuit of performance goals, such as greater strength or speed. The goal is often something more prosaic: recovery from injury.

“In some professional sports, I wouldn’t even call [performance enhancement] cheating, because everyone at a high level is using something,” argues Young. “It’s just this weird situation where, in some sports, in order to be a professional, you can’t be natural. You just can’t be. Not necessarily because you need to get bigger and stronger, but because the injuries will just destroy you if you don’t.”

Young believes we are either extremely naïve or staggeringly idealistic to assume or expect athletes to compete at the highest level without performance enhancement. “I think there’s a weird hypocrisy in audiences where we want athletes to be the fastest, the strongest, the best, the toughest, have the most perseverance. Well, okay, then what do you think they’re going to do in order to train and recover and do their best? What do you expect? That they’re going to go into it raw?”

What’s the alternative? Until recently, there hasn’t been one. But late last year a group of tech tycoons launched the Enhanced Games, the premise being that athletes should be allowed free rein to use PEDs. The idea is to push the limits of humanity, tapping into the wider biohacking movement that prizes optimisation in all areas of life.

The movement’s poster boy is former 100m swimmer and silver medallist at the London Olympics, Australia’s James Magnussen, who said earlier this year that he would be prepared to “juice to the gills” for significant financial return. Founder Aron D’Souza previously told Esquire Australia: “One of the secrets of our modern society is that the elite are medically enhanced – whether athletes or business tycoons or celebrities – and normal people are not. It is an information-deficit problem.”

At a philosophical level, Young is not opposed to the venture but does offer some caveats. “If everyone comes in with open eyes . . . well and good,” he says. “But in any kind of laissez-faire situation, you’ve got to be super careful about the harms that people will do to themselves because they’re not really in a place of rationality.”

And where do you draw the line, if you draw it at all? In the interests of athlete health, Young says, the Enhanced Games will surely have to impose a threshold on the use of certain substances. D’Souza has said athletes will be tested and screened year-round to mitigate health risks. “I don’t want an athlete to have a cardiac arrest in front of billions of people on television,” he told The Independent in June. “That wouldn’t make economic sense for us.”

But by imposing a line, however arbitrary, the organisers of the Enhanced Games open the door to the likelihood that some athletes will overstep that mark and try to conceal the extent of their use of PEDs, effectively cheating.

“You want to draw a line because the next question is always, well, where does that lead?” says Young. “Does it lead to people just completely destroying themselves in the service of success? They’re going to have to draw some lines; they’ll just draw them differently to the IOC.”

Shirvington, too, has doubts about the concept of a PED palooza. “I find it poorly thought through,” he says. “At what point do you say to everyone, ‘Well, you can clinically take this, but you’re not allowed to take that’? And then be able to detect whether someone is following the rules? You’re going to end up back where you were with a drug-testing regime.”

Nor does he see much merit or appeal in juiced-up athletes breaking world records. “I reckon I could run a really fast 100m downhill or on a bouncy track, but what does that actually mean?”

The Enhanced Games declined to comment for this story. Whether the concept becomes a reality remains to be seen. It’s certainly difficult to see it working without genuine superstars involved. Even then, would we want to watch them? For many of us, athletes are a projection of our hopes, dreams and, yes, fantasies. We want the best to astound us with their feats of speed and endurance – and, less thrillingly, their ability to return from a hamstring strain inside of three weeks. Without that implicit dynamic, you wonder if athletes don’t lose some of their lustre.

“I think most people like to pretend you don’t need to be on performance-enhancing drugs to be superhuman,” says Young. If this is the case, the irony of professional sport may be that to truly enjoy it, you need to be willing to deceive yourself.

Related:

Why isn’t drug-testing of athletes the same across all sports? An explainer

The countries that pay their athletes for winning Olympic medals