A surfer reviews 'The Surfer', a tragic parable about tribalism, masculinity and identity

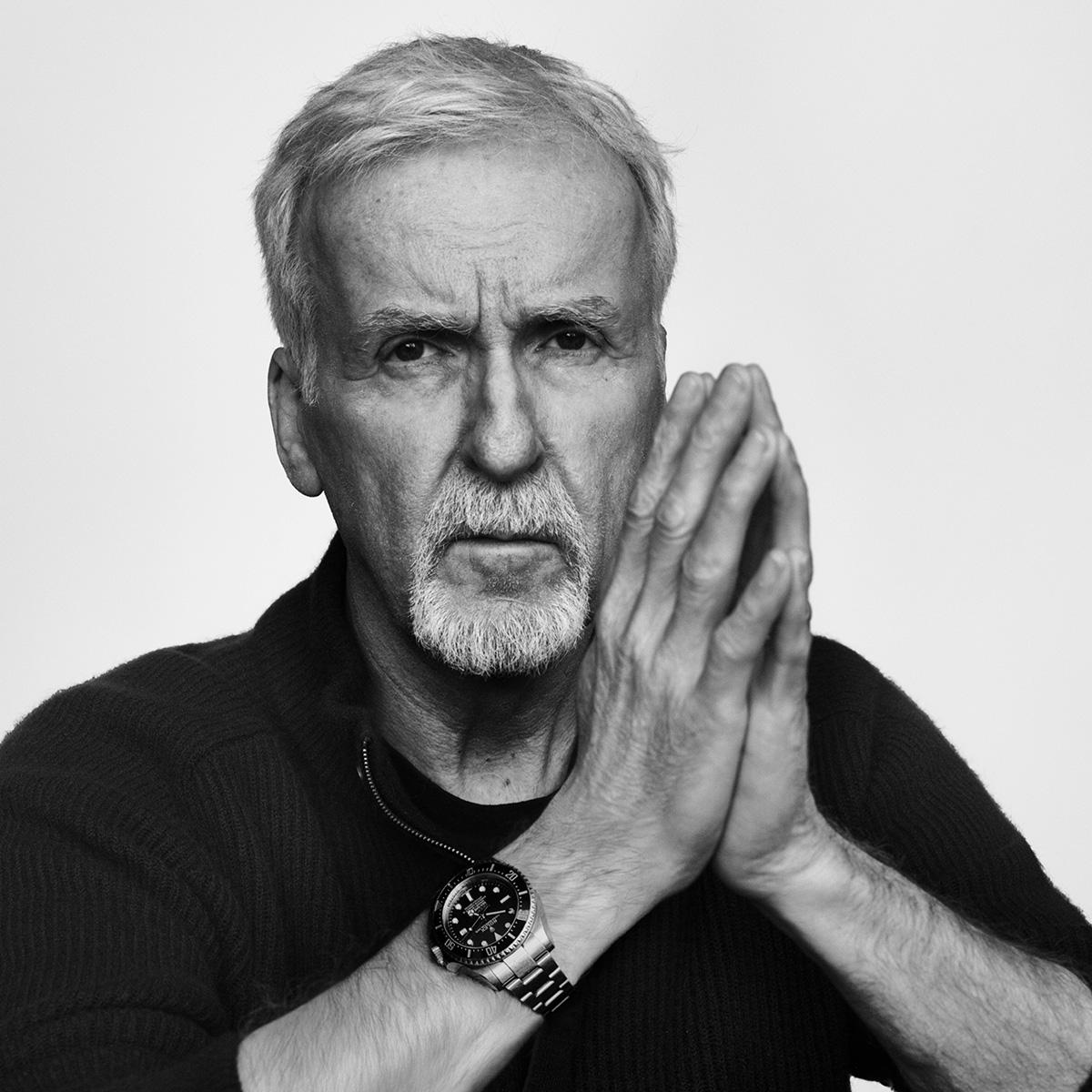

Nicholas Cage grimaces his way to insanity in this psychological thriller, where everything is not quite as it seems – or is it?

This review contains spoilers for The Surfer.

On the cliff above Bali’s Bingin Beach, there is an abandoned construction site with a view of the wave I travelled here to surf: a fast, veiny, barreling left-hander, dredging up from the reef like blood being pumped from the ocean’s lung. I watch as near symmetrical lines form in the cobalt distance. It’s the type of wave I’d seen photographed in surf magazines as a child, a beacon of crystalline perfection I imagine some opium addict dreamt up in his euphoric ravings.

What the websites and travel guides failed to tell me was how much human desperation there was in the scramble to get on this wave: seventy grown men battling for position on one single take-off spot the size of a linen closet. I paddle out, listening to the roar of the wave shattering on the reef, vying for an inside position. After half an hour of chess-like maneuvering, I finally have priority to take off as a set of waves approaches. Paddling hard to the inside, ready to spring to my feet and soar, I feel the nose of another board jab my arm, catch the grin of man before he pushes me aside and yells to a surfer beneath me to take-off. Later, back on shore, a very-tanned Portuguese surfer approaches and tells me a group of Russian surfers had paid a Balinese local to act as their surf guide and block waves for them. “A hitman,” he laughs as we climb the steep steps back up the cliff.

I thought of this memory often while watching Lorcan Finnegan’s The Surfer. In the opening scene, Nicolas Cage (linen suit, shit-eating grimace, American accent, all buttoned-up nervous energy) pulls into a sunlit coastal car park on a fictional Australian beach in a Lexus. He’s brought his son to surf Luna Bay, where he once learned how to ride waves as a kid. But just before reaching the water’s edge, Cage is stopped by one of the locals. “Don’t live here, don’t surf here,” says the man.

But Cage, high on woozy Endless Summer nostalgia, isn’t just here to surf. He’s returned to Luna Bay to buy a slice of beachfront real estate, convinced that it will somehow stitch his fractured family back together. What happens instead is a ritual humiliation and a merciless public hazing at the hands of the locals.

The ‘Bay Boys’, the local gang who mock, ridicule, and torture Cage towards insanity, were loosely inspired by the notorious Lunada Bay gang near Malibu. “These modernist houses above Lunada Bay are all owned by lawyers and hedge fund managers,” director Lorcan Finnegan tells me. “During the day, they talk to clients and present themselves as very public-facing. But once they hit the sand, they turn into this primal, tribalistic gang, obsessed with ownership of the beach.” It’s in this intersection of gentrification and tribalism that the film finds its pulse.

In being denied a wave and his dream property, Cage’s character is denied a kind of identity, the feeling of belonging. “Being told he doesn’t belong anymore is catastrophic for him.” Finnegan says. “He has to be stripped of all his material possessions and pride, going on this almost Jungian journey.”

In the rough vernacular of surf culture, Cage is a kook (deriving from kuk, Hawaiian for excrement): an adult-learner with too much money, not enough skill and no local cred. For the uninitiated, modern day localism in surfing is a cocktail of tribalism and xenophobia, bordering on complete paranoia as leathery white men paddle around with their antennae up on the lookout for any form of outsiderness. They speak wistfully about the days when the lineup was less crowded. The discussion is complicated by the fact that surfing was once a fringe subculture, something sacred and ancient and beautiful enough to be worth protecting from being instagrammed into oblivion.

What The Surfer gets right about contemporary surf culture is that the nostalgia for untroubled waters and isolated waves is alive, but not achievable, even for the ultra-rich (I recently heard Chris Hemsworth complain about his grommets being dropped in on). The ocean, with all its cobalt crests and sacred lore, becomes a stage for all our petty grievances. We don’t leave ourselves on the shore; we drag every grudge, every prejudice, right into the lineup with us. While Cage doesn’t even make it into the water, his character pins all his hopes and dreams on this fantasy of an idyllic beach life, only for his persona to shatter in the face of rejection, a journey that reaches its crescendo when his hunger drives him to eat a rat. (While the locals scream “EAT THE RAT!”, the tension of the scene was completely interrupted by roars of laughter in the cinema).

The film is less psychological thriller than a slow descent into the realm of myth and parable, an old story about psychic collapse when the idea of who you thought you were is denied, then slowly scrubbed away. When Cage eventually submits to the Bay Boy’s initiation in an attempt to gain access to the club, he burns down a homeless man’s car, his derelict living quarters. Cage’s son watches from the bushes. “That’s what the film is about, really,” Lorcan tells me, “intergenerational trauma, the passing down of these cycles of violence across generations and the kind of animalistic internal battle that goes on inside some people.”

Thinking back to the day out at Bingin Beach, I had shared a similar sentiment with Cage’s character, something soul-crushing and difficult to name. Maybe it was the weight of my disillusionment. I too was jaded and wave-hungry, still revering the surf as some Morning of The Earth-esque mythical past-time and not the post-globalized sport it had become. Maybe the days of courage and bravado, the respect for those who hustled hardest to climb the proverbial pecking order, had gone out the window.

In the end, I think The Surfer speaks to the pathetic ways men try to reclaim something they have lost. A lost idea of themselves, or a family, or a past that never existed to begin with. As for the final scene, which will leave you wondering what, exactly, you’ve just watched? “I think we’ve left just enough room in the structure of the film for the audience to be able to fill in those gaps themselves with their own perceptions and their own psychological meanderings,” Lorcan says. “It’s cerebral enough for people to take away what they will.”

The Surfer is currently in Australian cinemas, and streaming on Stan from June 15.

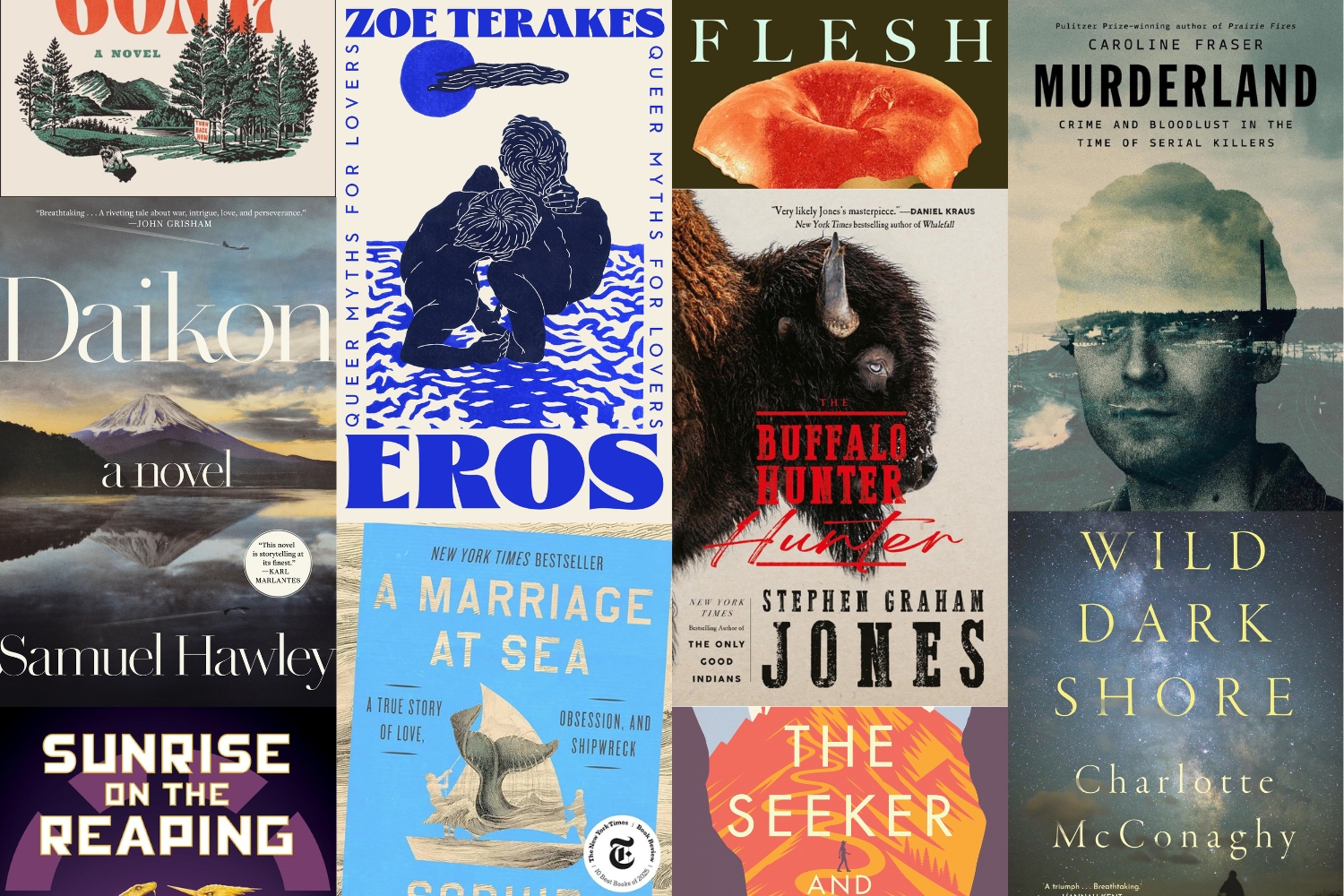

Related: