Achtung Vegas: the inside story of U2 at the Sphere

Within a giant, $2.3BN ball in the Nevada desert, U2 reinvent the rock concert, again. Is this the end of the world tour as we knew it, or even better than the real thing?

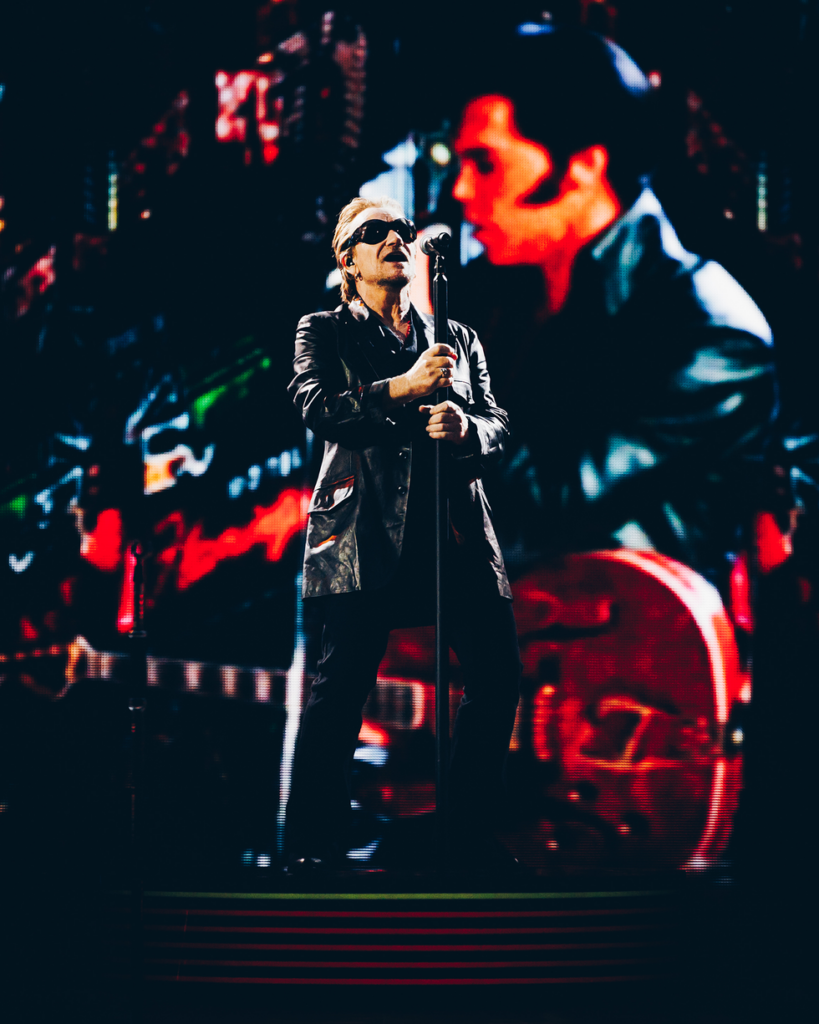

“WHAT A FANCY PAD,” says Bono, gazing around him from behind the old bug-eyed “Fly” shades he’d put on, with no little theatricality, a couple of songs earlier. “Look at all this… stuff!” the singer exclaims as he stands on a stage modelled on an artwork designed by Brian Eno (“Turntable”, 2021, acrylic, LED lights).

Packed below and above the 63-year-old in a well-behaved moshpit and steeply raked bleachers, 18,000 fans — tickets currently available from $400.21 — roar their agreement as the world’s biggest LED screen shimmers and hums. Just wait till they see the cascade of AI-generated Elvises and the vertigo-inducing torrent of binary code that makes the stage feel as if it is plummeting away from them. Rock’n’roll’n’algorithms.

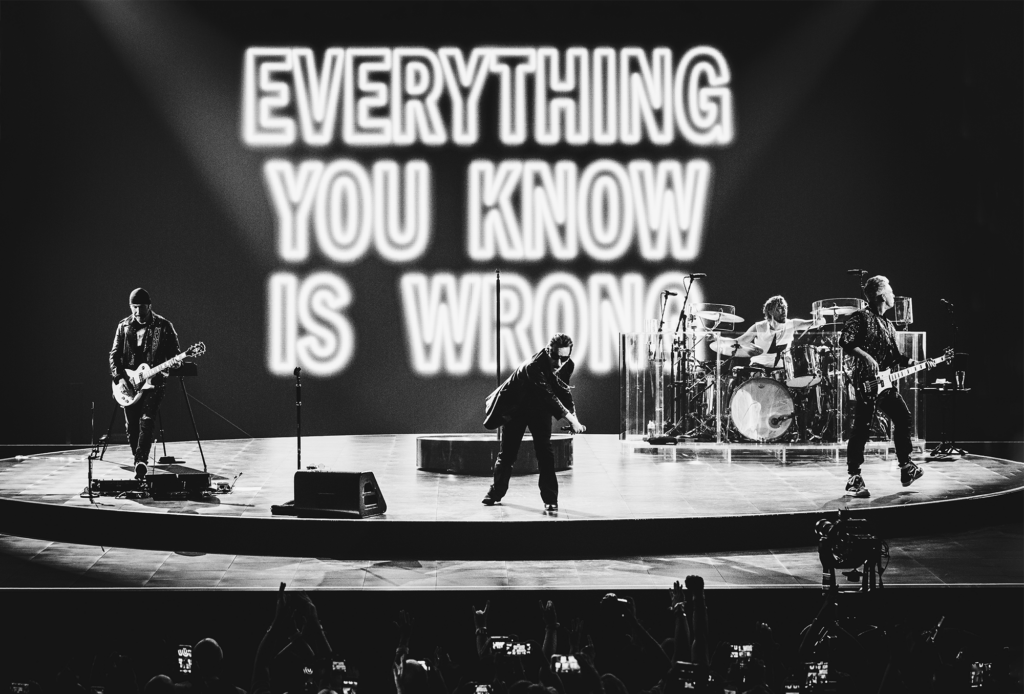

On Friday 29 September, as U2 kicked off their first live show in four years, the band’s new playroom did indeed contain a lot of stuff. And a lot of space in which to put that stuff: 5.7 million cubic feet, stretching 336ft into the desert sky, flexing 516ft wide on the Las Vegas strip.

This is the opening night of (deep breath) U2:UV Achtung Baby Live at Sphere. The Irish band’s residency in the planet’s self-proclaimed entertainment capital stretches over 25 shows and 11 weeks in a spanking new, $2.3bn venue connected, by a bespoke, covered and carpeted walkway, to The Venetian, one of the city’s sprawling gambling resorts.

But don’t imagine this is anything like the showbiz of the more traditional casino-booked turn currently on offer elsewhere in Vegas. There’s no jewellery-rattling from spenny bottle-serviced tables as Adele bangs out another weepie. No Rat Pack-channelling heritage à la Lady Gaga, belting her way through a show with the Ronseal title Jazz & Piano. No middle-aged meltdowns like those happening across town as Barry Manilow beats Elvis Presley’s record for a residency at the Westgate, as he did the week before U2 arrived, when his 637th show trumped The King’s 1969-76 run at the same venue.

In simple terms, U2’s Vegas offering is this: a 22-song, three-act anniversary celebration of 1991’s Achtung Baby, their seventh album, with some video cues from the accompanying — and at the time revolutionary — Zoo TV tour.

“When we made Zoo TV and [follow-up tour] PopMart, we opened the door through which the entire concert-touring industry followed,” Willie Williams, U2’s long-standing show director, tells me. “Every show out there now looks like a cross between Zoo TV and PopMart,” adds the touring veteran, as aware as anyone that 2023 is also the year of Beyoncé’s Renaissance and Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour mega-shows — not to mention Coldplay’s similarly titled and seemingly never-ending stadium slog, Music of the Spheres. “That’s fine; it’s flattering and it’s wonderful.”

The set comprises the Achtung Baby standards (“The Fly”, “One”, “Even Better Than the Real Thing”). An “ambient” bit in the middle featuring stripped-back versions of catalogue tracks selected for this year’s Songs of Surrendercollection. And a finale that romps through a brace of U2’s most anthemic ol’ faithfuls (“Elevation”, “Vertigo”, “Where the Streets Have No Name”, “With Or Without You”). All this performed in a freshly opened, sphere-shaped concert hall.

There the simplicity must end. This is a show underpinned by contributions from visual and conceptual artists (Eno, Es Devlin, Jenny Holzer, John Gerrard, Marco Brambilla, Industrial Light & Magic). Amplified by concert technology of unprecedented scale and innovation (160,000 speakers and a 160,000sq ft wraparound LED display with world-best, 16k-by-16k picture resolution). Bristling with messaging (excess, consumerism, the American Dream, species extinction). Supersized by a building that can seemingly dissolve its own walls so punters feel as if they’re hovering above the city or plonked in the desert. And philosophically fired by a mission to create an immersive gig experience like no other.

Rich Fury

Sphere, by some estimations the biggest spherical structure on earth, is even more grandiose on the outside. Its 580,000sq ft exterior LED display is constantly shifting and winking into the Nevada sky, variously displaying an eyeball, an emoji, blooms of jellyfish — and, inevitably, advertising. It’s as if U2 and Sphere mastermind James Dolan, the billionaire owner of Madison Square Garden and a host of sports franchises, are declaring with chest-puffing pomp: look on our stuff, ye Coldplay, and despair!

Putting on a multimedia concert spectacular that inaugurates both new performance paradigms and a $2.3bn big ball takes, well, big balls. Handily, U2 have never been afraid to be ballsy, whether it’s ripping up their epically successfully, but also epically windy, rock rulebook and coming back with the sturm und drang of Achtung Baby (a great thing), or that time they sent malware into 500m people’s iTunes libraries (um…).

Even so, the scale of U2:UV is less Chris Martin busting yoga moves on the B-stage than Alice Through the Looking Glass.

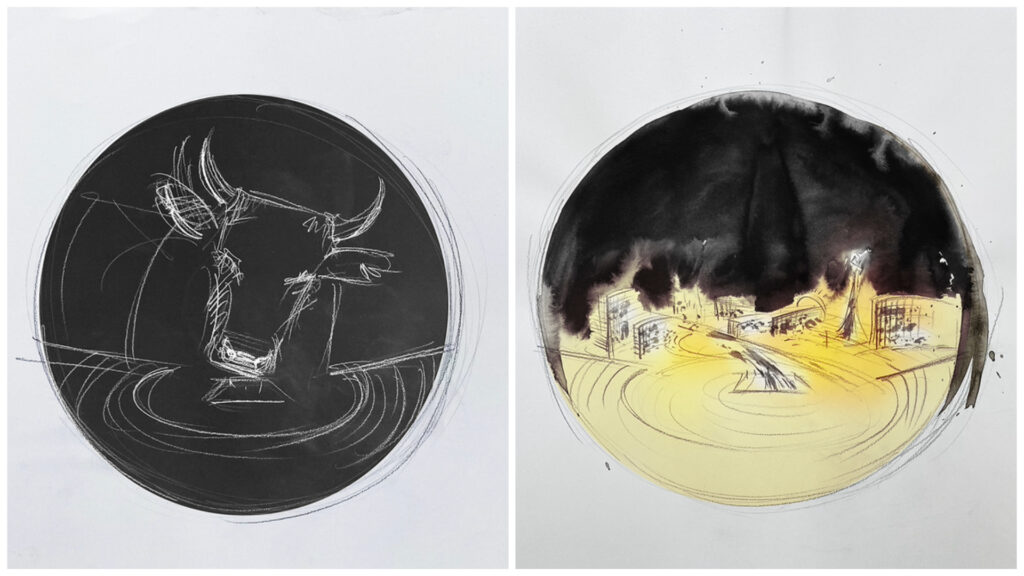

“It’s probably the most intimate stage they’ve done [in decades],” says Ric Lipson of London’s Stufish, who created the stage and set design, his assessment a reflection of Sphere’s vertiginous, amphitheatre-style construction. “There aren’t catwalks, there aren’t places for them to go — deliberately. That gave them a new language. It feels like you’re in a stadium but with the scale of a club.” A deeply experienced partner at a company calling itself “entertainment architects”, Lipson knows of what he speaks: he was also involved in the creation of another game-changing venue, the “demount-able and tourable” ABBA Voyage arena in East London.

The other big-ticket resident in what we’ll call Sphere’s opening season is a film by Darren Aronofsky (The Wrestler, The Whale), one designed to take advantage of that all-encompassing screen. The director has described Postcard from Earth as a “sci-fi journey deep into our future as our descendants reflect on our shared home”. The shooting of the feature had been “a learning process because the technology is new… Delivering a half-petabyte movie — that’s 500,000 gigabytes — that utilises more than 160,000 speakers is mind-boggling.” Just to ensure those bums on seats, Sphere will also bump those bums out of their seats: at appropriate moments in the film, haptics will make your perch vibrate, wobble and clunk.

This new venue, then, is aggressively conceptualised to assail all the senses. We should expect no less from the big-swinging but divisive Dolan — “one mad bastard”, Bono calls him, approvingly, from Sphere’s stage, a sentiment with which those sports fans barred from the Garden for criticising his ownership of their teams would undoubtedly agree. Although even U2 have to draw the line somewhere. “They can [pump] aromas and things like that in[to] the building,” says Williams, who has overseen every U2 show since 1982/3’s tour in support of third album War. “But I wouldn’t give that idea to a bunch of Irish guys.”

All of which begs the questions: how? Why? Really? And does U2:UV Achtung Baby Live at Sphere mean curtains for the world tour as we know it?

“To be candid,” begins bass player Adam Clayton, “we know that four guys playing instruments on their own after 50 or 60 years of rock’n’roll is not really as exciting as it used to be. You know, we serve the music. And we were interested in imagery that made the music bigger, or made the music more effective.”

When U2 come to Las Vegas determined to reimagine what a rock show could be, we’re inevitably a long way from Sinatra at the Sands. We’re even a long way from Calvin Harris’s blockbuster five-year residency with Hakkasan Group, a peak electronic-dance-music payday in which the DJ reupped the deal midway through for a reported £200m. That, after all, was just a tall Scottish bloke standing and playing records.

Rich Fury

Still, even the time-served frontman was initially overwhelmed by UUABLS, as no one is calling it. “How are you?” Bono, a showman used to projecting stadium-scale bromides, asked the audience early on in the band’s 130-minute show. “Where are we? Who are we?”

It seems that wasn’t just rock-star posturing. Williams admits that, in rehearsals, he’s had to help these seasoned road warriors with their bearings (those perhaps further wobbled by the absence, for the duration of this residency, of drummer Larry Mullen, who’s recovering from unspecified surgery). “They have to learn a new physicality,” the show director says. “I keep saying to them, ‘look up!’, because it’s an amphitheatre and a lot of the audience are up high. It’s much, much more contained.”

Clayton, too, is still getting his Sphere-legs. When I ask what the risks inherent in this show are for the musicians on stage, he replies: “Ha, that we fall over?”

According to the bass player, two things happened to get the U2:UV ball rolling. Firstly, in 2021, Achtung Baby reached its 30th anniversary. “And because we were in Covid, we went: oof, should we celebrate this record? And if so, should we do something like we did for The Joshua Tree?”

U2 celebrated that 1987 album with 2017 and 2019 tours that centred on new films made by long-standing collaborator Anton Corbijn. Given that that album’s original tour featured little fancy production per se, “we were able to completely redefine how people looked at that record,” says Clayton.

“But when we came to Achtung Baby, we [wondered]: how do you update the Zoo TV concept? Because all the predictions of Zoo TV have come to pass: fake news, media overload, the MTV generation, wars fought on television with camera systems that could follow a missile down the street, as it was in the Iraq-Kuwait war at that time. So we just thought: we can’t take this out [on the road].”

Fortunately, they then heard about “this thing called Sphere being developed”. Here, perhaps, was a place, a building, where the band could do to the concert experience what Bono described Achtung Baby as doing to the studio album that preceded it: “The sound of four men chopping down The Joshua Tree.” Even though the singer now admits, in U2:UV’s coffee-table tour-programme, that he said that “because it was a mouthy, headline-grabbing singer thing to say,” the band agreed the idea was worth exploring.

As Clayton puts it: “What was interesting about that was, after 50 years of entertainment and concert revenues being generated, finally someone said: ‘Let’s make a building where music sounds good. Where we’re not in a sports arena that isn’t designed for music.’”

Not everyone in Team U2 was immediately sold on the idea. When Williams heard, 18 months ago, about the idea of U2 performing at a long-delayed, over-budget, as-yet-incomplete, as-yet-unproven new concept for a venue in Las Vegas, he thought: bad idea, bad location.

The band has to learn a new physicality. I keep saying to them, ‘look up!’ because a lot of the audience are up high

“I’ve never liked this place,” he grumbles from his Las Vegas hotel room four days before showtime. “I find it very dark. And, these days, increasingly cynical. It seems people come here because they’ve seen it on Instagram. When Vegas was cheap, it was one thing. But now Vegas is really expensive.”

Equally, and unusually for a U2 show, this idea would mean they were beginning with the canvas, not the art, “which never usually works”. In other words: “the only given at the beginning was the hardware,” Williams says, meaning the still-under-construction venue. “And I was quite resistant. Nothing about this did I think was a good idea. Also, the scale of it seemed completely wrong — unlike, say, Innocence and Experience,” he says of U2’s 2015 tour, in which the stage and parallel screens ran the length of arena floors, “where the humans, the performers, really related in size to the video images. This just seemed completely whack.

“But,” he adds, brightening, “the opportunity then is: if you present something that is genuinely joyful and light-filled, people respond incredibly well to it.”

Marco Brambilla was one of those tasked with bringing that light. To accompany U2’s performance of “Even Better Than the Real Thing”, the Italian-born, London-based Canadian video collagist created a psychedelic kaleidoscope of The King. “King Size” is a sweeping, swooping digital mural of Elvis Presley featuring AI-generated images from every stage of his life, all 33 of his films, and assorted pops of Las Vegas iconography — the better to get over the idea, says the artist, that “both Elvis and Vegas were metaphors for the epic trajectory of the American Dream”.

Recalling his commission conversation — which happened as recently as this spring — Brambilla says the band told him “this song, to us, represents maximalism and spectacle. We want [the video piece] to be hyper-realistic and dense and take full advantage of the size of Sphere.”

Rich Fury

It’s job emphatically done. Brambilla’s work is an eye-popping, senses-scrambling wonder, floods of Elvises raining down from the top of Sphere. With “Even Better Than the Real Thing” appearing as the third song in the set, this marriage of song and visuals is early, decisive, brilliant proof-of-concept.

But U2:UV is far from done with its wonders. For “Who’s Gonna Ride Your Wild Horses”, towards the end of the first act, the musicians appear like gods in the sky, their pin-sharp likenesses towering above the audience, a 16k-by-16k version of The Jacksons’ “Can You Feel It” pop video meets Jason and the Argonauts. For “Until the End of the World” Irish artist John Gerrard, who creates digital likenesses of flags, has reworked a pre-existing piece: “Flare” is a billowing plume of burning oil, as if spewing from a desert well. There’s a new piece, too, “Surrender”, for “Where The Streets Have No Name”, clouds of water vapour creating a giant, stirring white flag.

Both of Gerrard’s pieces, says Clayton, have pointed meaning. “Flare” speaks to “U2’s relationship with the desert with Joshua Tree, but also where we are in terms of climate responsibility. And ‘Surrender’ is… set in the ocean, where the ocean is the warmest it’s ever been due to climate change. So there’s these little references. To be honest, they’re poetic,” he acknowledges. “But they’re deeply, deeply emotional.”

Es Devlin’s contributions make those points, too. For the climax of U2:UV, the acclaimed English stage designer has created “Nevada Ark”. It’s a version of her 2022 Tate Modern piece “Come Home Again”, “which was me drawing 243 endangered species of London”. Bono saw that show, rang her up and said: “Why don’t you do that for the species of Nevada?”

So, she tells me, “the whole Sphere gets filled with these [likenesses] of stone carvings”. In fact, the Crescent Dunes Serican Scarab beetle, Ash Springs Riffle beetle, Devils Hole pupfish, Sand Mountain blue butterfly and 22 other extinction-threatened species have been lovingly crafted out of pixels. “It’s like looking up in the Alhambra, into this cathedral. Then when you come out of the building, they’re all over the outside, too.”

She wasn’t exaggerating. Devlin’s at-risk animal house, carpeting the dome’s vaulting interior, is an astonishing, breathtaking end-point for U2:UV — a powerful moment of celebration and reflection as, appropriately enough, the final song “Beautiful Day” fades away.

All things considered, as gigs go, it’s even better than the real thing.

There is plenty more to come as Vegas doubles down on maximalist entertainment. In November, the Formula 1 Grand Prix circuit makes a desert pit-stop, with the track roaring through Sphere’s parking lot. U2’s show — launched by the band with a punky new song, “Atomic City”, named after the town’s nickname in the good old days of nearby nuclear tests — is running all the way to the week before Christmas. There it overlaps with, and hands over the bombastic baton to, the 50,000sq ft LIV Nightclub at The Fontainebleau, scheduled to open on 13 December. It’s a “vertically integrated” resort with 67 storeys, 3,644 guest rooms, 36 restaurants and bars, and a casino with 42ft-high ceilings. It’s taken even longer to imagineer (ground was broken on construction in 2007) and cost even more ($3.7bn) than Sphere.

Meanwhile, that traditional benchmark of Vegas performance, the casino residency, continues to pull in high-rollers and low-rollers alike. Usher has been packing them in since April at Park MGM. Weekends with Adele at Caesars Palace’s Colosseum theatre has been running for a year, finally sobbing to a close in November. There’s another handover that weekend: the night before Adele ends, Kylie launches her residency at The Venetian, christening the resort’s next new venue, Voltaire. A bijou, 1,000-capacity spot, it will apparently lead a “revival in high-calibre nightlife”.

But right now, Sin City belongs to U2. Going by my experience of opening night, and by most of the reviews, the show fulfils the lofty goals of everyone involved. Like ABBA Voyage, it’s a whole new kind of gig experience. If you build it, they will come — and the live music industry will need to pay heed. After all, as Clayton says: “The days of a bunch of hairy guys standing up there and playing rock’n’roll are probably limited. We live in a world where the young and the beautiful dominate. Because it’s all about the image.”

Devlin, certainly, sees the need for change, and not just from the point of view of the carbon footprint of hauling a huge production country to country — Beyoncé’s Renaissance tour-credits list 80 truck drivers, their artics melting the Arctic.

“If you think how long opera or theatre have had to evolve as mediums, this is a young art form,” she says. “The distance between the first [big] pop concert, which you might argue was the Shea Stadium debacle, where The Beatles could barely be seen or heard, and were practically mobbed by the size of the audience, is only 60 years,” Devlin adds. It’s a comparison Bono also makes from the stage: “I’m thinking the Sphere may have come into existence trying to solve the problem The Beatles started at Shea Stadium in 1965. Nobody could hear you and you couldn’t hear yourselves.”

So: does the advent of U2:UV Achtung Baby Live at Sphere — a band, parking themselves in one place for months, leaving no performance element to chance — mean the beginning of the end for the traditional world tour?

The days of a bunch of hairy guys standing up there playing rock’n’roll are probably limited. it’s all about the image

“I doubt it. I cannot imagine how anybody else will ever be able to play in this building,” says Willie Williams, although Jim “Mad Bastard” Dolan is on record as saying he has the next two acts booked (“big names”, apparently). “Because U2 spent 18 months [conceptualising], and we’ve had two months in the building. Now, admittedly, the building was still being built! But creating for this space is so bespoke. The commitment required, creative, intellectual, financial… I find it very hard to imagine how anybody else could play here.”

Devlin concurs about the defiant viability of touring, albeit for different reasons. For one thing, she understands that flying into Vegas to see a favourite artist is beyond the financial reach of most fans. For another, artists themselves want to be out in, and of, the world. Having worked on The Weeknd’s current After Hours Til Dawn stadium trek, each night she watched Abel Tesfaye “finding people in the crowd with a very specific energy, and responding to that energy, then going to the other end of the stadium and becoming a conduit for one group of humans’ energy over to the other side. That will continue.”

Equally, too, what Williams calls the “kinetic energy” of touring is crucial for artists. I ask Adam Clayton about that. Does his band’s necessarily precision-drilled new show allow for momentum and looseness? In their cavernous ball-pit, is there still room for U2 to, in every sense, play?

“I hope so!” the musician answers, laughing. “Or I’m going home!” ○

U2:UV Achtung Baby Live at Sphere, Las Vegas, runs until 16 December

Related:

Everything we know about Jacob Elordi’s new film, ‘Saltburn’

First trailer arrives for apocalyptic thriller ‘Leave the World Behind’