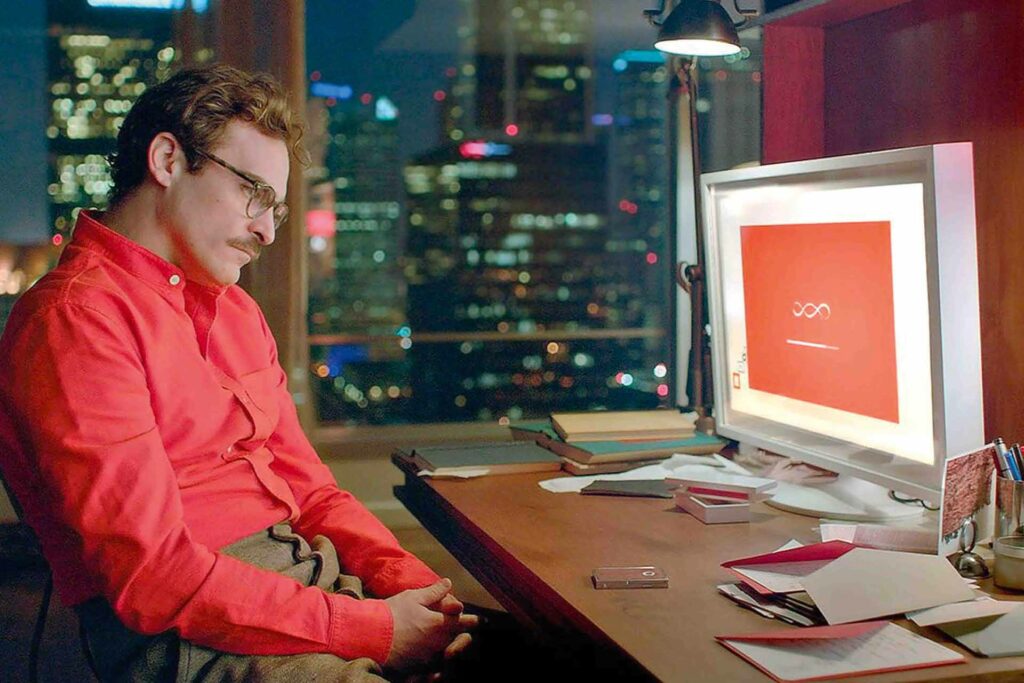

Could a robot write this column better than me?

As someone who earns a living from writing, Jonathan Seidler isn’t immune to the growing threat of AI. But he’s not convinced the machines are capable of imitating his original thoughts and prose—yet.

Jonathan Seidler is an Australian writer. This is his column for Esquire.

THERE ARE CERTAIN THINGS in life that are a given. For instance: if you’re a doctor at a party, someone is going to approach you, tell you about their ailment and ask you to diagnose it. And if you’re a writer like me, after approximately 3.8 standard drinks, some guy is going to throw their arm around you, swear a bit unnecessarily and then ask you how you feel about the staggering rise of artificial intelligence.

Never mind that our robot overlords are far more likely to automate the jobs of many other disciplines before mine—those swathes of lawyers, accountants, marketers and middle managers that make up the bulk of knowledge workers. Without doubt, it’s easier to get a machine to do a job that requires lots of process and very little original thought. It’s just not as juicy a question, I imagine, to ask a paralegal how they feel about the fact that right now, a sophisticated machine is teaching itself everything they sweated five years of uni and umpteen hours of overtime to learn than it is, say, to stare wide-eyed at someone who makes a living writing about their ideas and wonder how we will survive a sentient bot that can spit them out better than we can.

I’ve had two brushes with AI in recent weeks, both of which have been hilarious and so bizarre that not even ChatGPT could’ve scripted them. The first is that I read a job description for a creative role in which the understanding of how to use AI tools was a key component. This is a bit like asking someone on the wrong side of the Mafia if they are proficient in tying laces on cement shoes before they go for a swim in the harbour.

The other was a former employer who brought me back in to cover some work in a freelance capacity, only to reveal that they’d been feeding my former writing through AI to generate new material while I’d been off doing other things. This is fun because I now get to compete with a highly sophisticated robot version of myself. It is the ultimate test of ego, one which I will surely lose, but it will make great fodder for the next party I go to.

To be clear, I’m all for the rise of the machines. Midjourney yourselves to death, I say; the sooner we let the computers take over, the sooner we bring in Universal Basic Income and I can spend my days playing drums in bands just for shits and teaching my daughter to surf without ever worrying about a deadline again. But since that looks like it might be a fair while off, and since every apparently amazing script and short story I’ve read cranked out by a machine still looks like it was the work of an Estonian trying to speak fun, breezy English through Google Translator, I guess I have to share my bed with this string of code and suck it up.

The question now is whether I should start going all Screen Actors Guild on everyone I work with, building in a fee for the potential of my work to be extrapolated, boolean style into the future. Call it AIT, Artificial Intelligence Tax. The problem with being a working writer, as opposed to someone who makes money but doesn’t make anything a computer really cares about, is that we provide endless source material for the mulching garbage bin of AI. There’s actually nothing stopping some 19-year-old who knows how to write prompts grabbing this and the other 25 columns—not counting features—that I’ve written for Esquire and setting up a virtual rival tomorrow. Lord knows we probably have some nefarious actors out there in the world of men’s culture media.

To test this, I asked my wife, who often uses ChatGPT to help with shortcuts and summaries at work, to see how much of me was already sitting in the Matrix. And so I present to you an extract of what was provided when it was given the prompt ‘write me a story of the beach in the style of Jonno Seidler’.

“Seaside Reverie: A Jonno Seidler-esque Exploration of the Beach”, it began.

The sand, a mosaic beneath our feet, whispers stories of the ocean’s ancient rendezvous with the land. Seidler’s pen would elevate the ordinary grains to eloquent narrators, divulging secrets of lost shipwrecks and forgotten footprints that vanished like fleeting memories in the vastness of the shoreline.

And then there are the surfers, modern-day poets riding liquid poetry. Seidler’s keen observation would illuminate the symbiosis between man and wave, capturing the unspoken dialogue between surfer and sea. The surfboards become vessels of expression, navigating the ever-changing topography of the ocean with a grace that mirrors Seidler’s linguistic finesse.

The coastal breeze carries with it a medley of scents—salt, sunscreen, and the subtle aroma of nearby food stalls. Seidler’s words would dance with the fragrance, encapsulating the essence of the beach in every breath, inviting readers to vicariously taste the salt on their lips and feel the warmth of the sun on their skin.

I’m known to write these columns fast, but this came out in 45 seconds. I think it might be time to retire at the ripe old age of 36. I cannot possibly eclipse such overwrought prose. But listen, before I do, can you just have a quick look at this strange discolouration I have on my neck?

Jonathan Seidler is an Australian writer, father and nu-metal apologist. He is the author of a memoir called It’s A Shame About Ray and a novel titled All the Beautiful Things You Love, to be published in April 2024. Jonno has some interesting things to say about music, fatherhood, Aussie culture, mental health, problematic faves and the social gymnastics of group chats. This is his column for Esquire. You can see all of Jonno’s previous columns here.