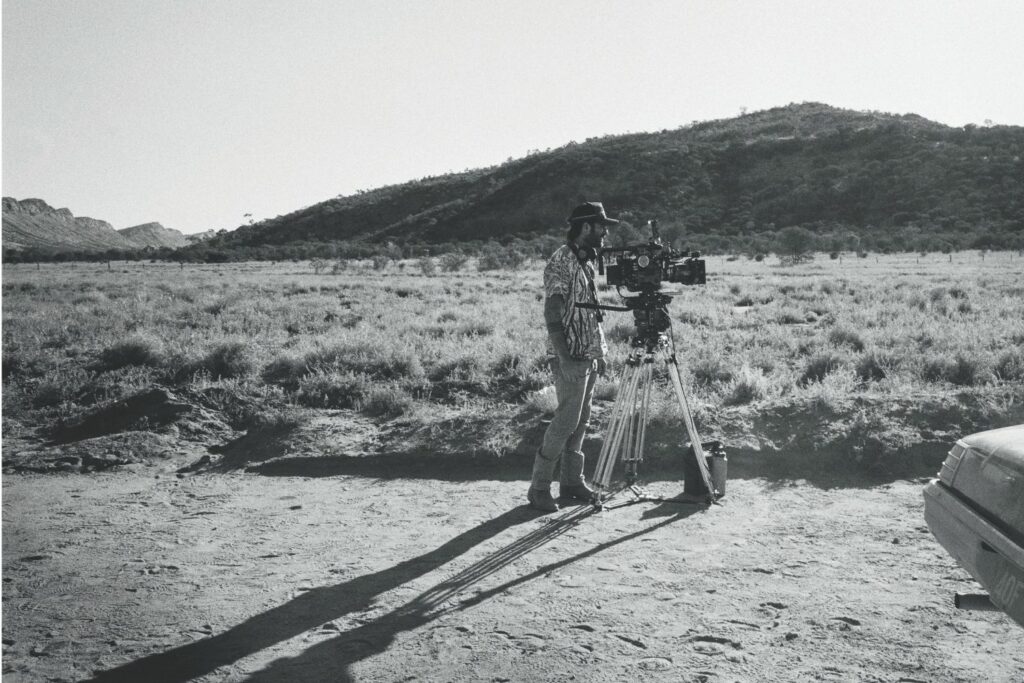

Dylan River, the auteur from Alice

Dylan River is one of Australia’s most exciting young filmmakers. The Kaytetye man’s latest project, set in Central Australia during the ’80s, is a black comedy about two young people on the run – from incarceration, and a sex worker whose taxi they stole

A CLUSTER OF golden AACTA statuettes sits in the corner of Dylan River’s study. The young filmmaker has won five in total, claiming his first, the Best Short Film award for Nulla Nulla, in 2015 when he was just 23. Gathered next to the statuettes is a bunch of film slates. “Yeah, it’s a thing,” he smiles when I point them out. “My family collects slates from our films, so that we have something [tangible].”

River, now 32, is part of an Australian filmmaking dynasty. His mother is Penelope McDonald, the award-winning producer and director, and his father is Warwick Thornton, the highly decorated director, screenwriter and cinematographer. Like his father, River is a Kaytetye man, born and raised in Alice Springs (Mparntwe). Already, he’s following in his parents’ critically lauded footsteps.

“We’re actually a very competitive family,” he says. “We’re all trying to outdo each other with what we do and what we make. We support each other – it’s just a big competition of who can make the best film.”

While cinematography was his first love, among River’s directorial projects are a documentary about motorbike racing, a short film about a white policeman in a remote Indigenous community, and, most recently, an AACTA-winning episode of The Australian Wars (2022), an SBS series that explores battles fought between First Nations Australians and British colonialists, reframing the narrative of how our nation was formed. Also in 2022, River joined the directorial team of Mystery Road, the acclaimed Australian franchise helmed by directors Ivan Sen, Rachel Perkins, Wayne Blair and Thornton before him.

Titled Thou Shalt Not Steal, his latest project follows Robyn, a young Aboriginal woman who’s fleeing detention, and her accidental sidekick, the awkward teen Gidge (both Robyn and Gidge are played by Heartbreak High alumni: Sherry-Lee Watson and Will McDonald, respectively). Hunting down Robyn’s family secret, the pair are chased through the desert by a sex worker who wants her taxi back and Gidge’s dodgy preacher dad (a duo played by veteran Aussie actors Miranda Otto and Noah Taylor). The off-kilter black comedy-thriller is something of an evolution of River’s 2019 web series, Robbie Hood, about a mischievous 13-year-old boy.

“I was definitely looking at Aboriginal political issues, but through comedy . . . sort of like bent, twisted ways of looking at some dire situations,” River says of both series, which were filmed and set in and around Alice Springs. He’s plain-spoken, but passion blooms when he speaks about his home. “Anyone else who comes and makes things [here], I’m always looking, going, Who are they? What are they doing? What are they making?” he tells me with a chuckle. “You know – What do they know about this town?”

As a teenager, River witnessed firsthand the vast potential that filmmaking has for engendering empathy, with the rapturous reception afforded to his father’s debut feature film, Samson & Delilah (2009). “I saw the power in what he did. You know, I saw people walking out of the cinemas, crying and being moved by his stories.”

The film painted a complex but tender portrait of modern life in the desert. At the time, the Northern Territory was two years into the Intervention – or Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) – a contentious package of federal-government measures that targeted more than 70 regional Indigenous communities. While its advocates justified NTER as a necessary response to high levels of family violence within those communities, critics characterised it as yet another example of coercive, knee-jerk and demonising paternalism. “That was all a big movement at that time,” River says. “It made me look at the importance of what my parents do, and [think] that I would like to have a legacy and contribute to that,” River recalls.

Thou Shalt Not Steal is set in the ‘80s, but River hopes it speaks to contemporary viewers, just like Samson & Delilah did 15 years ago. “To tell stories about Alice Springs that are fun and positive, with a little political spin, is really important to me – especially to bring this town out of where we currently are, and have more people come and visit and experience it,” he says, nodding to the harsh spotlight his hometown has been recently thrust into, following the passing of controversial curfew and alcohol laws

by the Northern Territory parliament earlier this year.

Not just a love letter to the desert River calls home, the series is also a telling glimpse into the filmmaker’s upbringing, revisiting the one theme he just can’t steer clear of: fatherhood. “Whether it’s a father you’ve never met and you’re running towards them, or it’s a father you’ve got that you don’t like who you’re running away from, I think that’s something that I tend to keep exploring in my work, very subconsciously,” he admits. “It’s only when I’m halfway through it I go, Ah shit, I’ve done it again. It’s about dads, isn’t it?”

In his work, River is still grappling with his early relationship with his dad. “I was a young boy myself whose dad wasn’t around a lot, and I only realised afterwards that I was writing my own story, about wanting my own dad to be around more,” he said in 2019, speaking about Robbie Hood. In reality, however, Thornton and River’s bond isn’t so fraught. “I just show him what I’ve made like a kid with their homework – like, ‘Look what I did!’ You know, he’ll watch it, and he’ll cry, and he’ll give me a hug,” River tells me, smiling. “And now it’s funny, because the same thing goes with him. He’s like, ‘Dylan, come and watch what I made!’”

River has learned to quiet the inner critic that whispered things like ‘nepotism’ in his ear as he began to receive funded opportunities. “You’re just getting given this because of your dad’s success, and you need to earn it,” the devil on his shoulder would tell him. “So, I’ve kind of spent the last 15 years constantly trying to prove to myself that I’m my own filmmaker, I’ve got my own voice, and I deserve the opportunities.”

The truth is, preferential treatment wouldn’t come easily because of the type of person his dad is – a witty yet gruff creative, not a schmoozing industry networker. “It’s funny. People who do know him would know that he wouldn’t be able to get me an opportunity. He doesn’t even know how to do an application,”

laughs River.

With such a celebrated family, it’s unsurprising that the concept of legacy lingers in River’s mind. “Yeah, it’s definitely something I’ve thought about – like, What is my visual language? What sets me apart or what do I contribute that’s unique? But I’m still working that out. It’s definitely something I’m not deliberately trying to do,” he tells me. He’d rather allow it to come naturally as he continues to expand his oeuvre – perhaps trying out horror and definitely making his own feature film. Anything is on the table, as long as it speaks to him.

“I often make things primarily for me,” he admits. “You gotta be true to something, and that’s what I try to be true to – make it for me, and if I make it for me, I’ll be making it for Alice Springs. I’ll be making it for people with similar experiences to me, and then that will extend, that will grow. If you make something authentic, there’s someone out there who will find that authenticity in it for themselves.”

Thou Shalt Not Steal premieres October 17, only on Stan

Related: