In 'Maestra'—sorry, ‘Maestro’—Carey Mulligan gives a truly bravura performance

Bradley Cooper’s film may be a biopic of celebrated American composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, but it is his wife, Felicia, who sets the tempo.

LEONARD BERNSTEIN’S first moment of professional glory came, through no fault of his own, at the expense of someone else’s. On 14 November, 1943, 25-year-old Bernstein was woken up by a surprise phone call: Bruno Walter, who was due to be conducting the New York Philharmonic Orchestra at Carnegie Hall that afternoon, had come down with the flu. Would Bernstein, who – at least as far as Bradley Cooper’s new biopic, Maestro, has it—was at that moment in a darkened bedroom with a male companion, be willing to step in at short notice? Bernstein leapt up, threw back the curtain from a huge proscenium window and let the opportunity flood in. While Walter stayed home and snuffled for breath, Bernstein launched himself into the stratosphere.

Maestro, which covers Bernstein’s incredible career as a conductor, composer and musician—but focuses on his even more incredible marriage to actress Felicia Montealegre Cohen, played by Carey Mulligan—spends a lot of time thinking about who is taking oxygen from whom. You might think that the title has made its intentions clear: that this is a story of a great man, told by another fine fellow with aspirations; Bradley Cooper not only directed and, with Josh Singer, co-wrote the movie, but also takes the title role (though we hesitate to use the word “lead”). Yet, to its creator’s credit, Maestro explores the nuances of the Bernsteins’ unusual relationship with a care and a thoughtfulness that is rare in the movies these days – and even more so in biopics, which so often feel compelled to swing for hagiography or hack job.

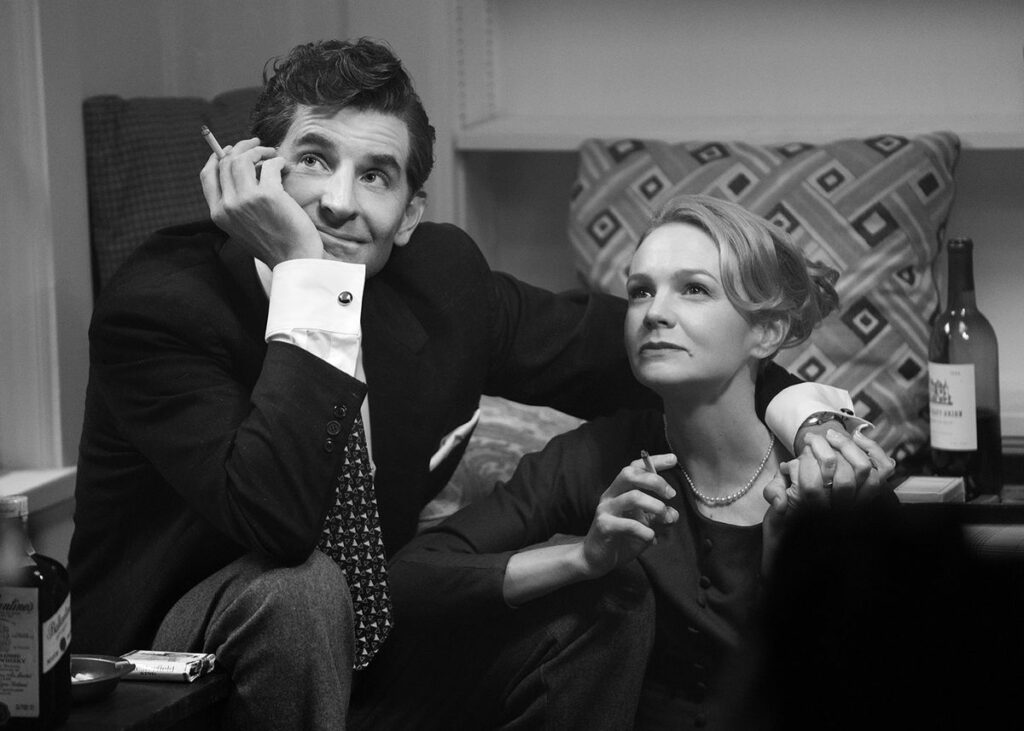

Early on, after they’re introduced at a party, Lenny and Felicia are full of vim and ambition: they speak with clipped, old-timey diction and they look at each other with starry, amazed eyes. There’s a parity—a sense that their shared sense of being the mixed-up, multi-talented children of immigrants gives them a looseness of identity that is unique, and that they must endeavour to preserve at all costs. “The world wants us to be only one thing, and I find that deplorable,” Leonard tells Felicia, before they launch into a brief La-La-Land-style dance sequence that is not so much dazzling (for all his talents, Cooper’s no Gene Kelly) as it is sweet.

The trouble is that Lenny is so intent on preserving his sense of self—his professional talent and also his ability to “love” others, widely and often (at one point he tells a newborn baby “I’ve slept with both your parents!”)—that he often fails to notice quite who he is taking down as collateral. As Leonard continues to “self-actualise”—not a term he would have used, of course, but a theme of the film that chimes nicely with the pervasive narcissism of our current age—Felicia gradually, almost imperceptibly, starts to disappear.

Here they are side by side at home on the sofa, being interviewed for The Ed Sullivan Show over a live camera link-up. Though Sullivan attempts to split his questions between them both, it’s Lenny he’s really interested in; gradually the shot tightens, and Felicia is edged from the frame. When Lenny rushes in to tell his family that he has finished composing his Mass, Felicia leaves the room; from a distance we see her jump into the pool fully clothed, so small she’s almost a speck.

This, in itself, is not such an unusual idea at the moment. We are in a welcome era of untold stories—of looking beyond the achievements of the Great White Men who have dominated our political and cultural histories in the West, and examining the figures who loved them, or helped them, or sacrificed themselves so they could thrive—Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla, about Elvis Presley’s young, neglected wife, being an obvious comparable example. But while Priscilla is consigned to a kind of domestic prison in which she can only pad about the shagpile carpets and drape herself into exquisite, sad tableaux, Felicia is both self-possessed and self-aware enough to see what is happening, and to articulate it to her husband (Maestro, also in contrast to Priscilla, gets to benefit from Bernstein’s music: go see it in the cinema if you can, and hear those concertos rumble through the floor).

In a brilliantly constructed scene, which takes place in the Bernsteins’ apartment as the gigantic inflated characters of the Thanksgiving Parade bob past the window, Felicia outlines to Lenny exactly the price she has paid. But she also confirms to him that she loves him, as he does her, and that despite the unconventionality of their marriage – she knows of his male lovers, but is only enraged when he becomes indiscreet—theirs is a bond that has weight and meaning beyond the brilliance that it facilitates (not least in the three children it produced; whatever his shortcomings as a husband, Bernstein is portrayed as a warm and involved father).

Netflix

As might be becoming clear by now, it is Felicia who gets to define the terms by which, whatever our initial assumptions, we understand the Bernsteins’ relationship. And, accordingly, it is Carey Mulligan who gets to define this film. While Cooper is charming and engaging (and occasionally very sweaty) as Lenny—and no, the nose is completely—it is Mulligan who provides the bass notes here in a performance that is magnetic and steely when it needs to be and, later, devastatingly fragile.

As far as the stylistic choices for Maestro go, and perhaps in recognition of Bernstein’s proclamation that you don’t have to be “only one thing”, Cooper goes for broke. He flips from black-and-white in the early years to saturated colour for the later ones; and if, just like Bernstein dabbling in musical theatre (West Side Story!) and film scores (On The Waterfront!), Cooper feels like throwing in a bit of head-spinning film trickery—at one point we follow Leonard from above, running through corridors with cutaway ceilings that lead him straight from his bedroom to the stage—then by golly he will.

But there is one particular shot that stays in the mind, and suggests that, as a film-maker, young Cooper is coming into his own (particularly heartening for anyone who found his A Star Is Born remake debut a little cloying). It’s not particularly subtle, but it’s indelibly striking, and it gets to the point. It’s from the Bernsteins’ early years, so it’s black-and-white: Lenny is on stage conducting and Felicia, as always, is watching from the wings. All we see of him is his giant silhouette, which is engulfing her, its arms thrashing wildly. She, in a silk evening dress and gloves, is a perfect, still, sliver of white in the centre of his shadow. He is making all the noise, but she is holding the frame.

‘Maestro’ is out in cinemas on 24 November and on Netflix from 20 December

A version of this story originally appeared on Esquire UK.

Related:

Bradley Cooper transforms into American composer Leonard Bernstein for ‘Maestro’ film

Jacob Elordi’s Valentino-designed ‘Priscilla’ costuming is impeccable