The Godfather Part II at 50: When Scorsese almost stepped into Coppola’s shoes

Could Marty have done a better job? One word: Fuggedaboutit!

THERE’S ONE THING great actors, footballers and movies all have in common: it’s a rare thing indeed to find a second stab that’s better than the original. You might say it of Ben Stiller and his father Jerry, or of Erling Haaland and his dad Alfie. You could argue a case for Terminator 2, The Empire Strikes Back and The Dark Night.

But there’s one product of greatness that unequivocally surpasses its progenitor: The Godfather Part II – Francis Ford Coppola’s sweeping masterpiece that set a new tone for cinematic storytelling.

That’s not to say Part I isn’t a work of undeniable genius in itself. It moves faster, shocks harder, and has Marlon Brando delivering arguably the most famous line in movie history about the art of the offer. But if Part I dazzles, Part II lingers. Michael unearthing Fredo’s betrayal is as shocking as the Don’s realisation over who his real enemy is. But when it comes to icy glances, Michael’s feigned forgiveness of Fredo, as his brother collapses pathetically into his arms, followed by that barely perceptible nod to his bodyguard, has to be one of the greatest moments in cinematic history. Never was so much said by a single flicker of the eyes.

We’re not here to dish out hot takes – the internet has more than enough of those already. It’s been 50 years since The Godfather Part II came out, and we’re here to talk about the sliding-doors moment that could have changed the course of mobster movie history forever: when Francis Ford Coppola tried to get Martin Scorsese to direct it instead of him.

Coppola was done with the Don

Coppola didn’t want to make a sequel to his 1972 Oscar-winning blockbuster. By the time filming wrapped, his relationship with Paramount Pictures had grown more strained than Marlon Brando’s voice must’ve been after playing Vito for nine months straight.

“I didn’t get along with (producer) Bob Evans during The Godfather, at all,” he told Deadline in 2019. “He was so tough on me. I was seriously on the verge of getting fired maybe on three or four occasions.”

Trouble was, Coppola not only went on to win Paramount an Oscar for The Godfather, but he’d made the studio some $290 million in the box office.

“When The Godfather fooled everyone and was this colossal success, they came to me and said, ‘Of course we want to make Michael Corleone Returns, because it made money,” he added. “I said I didn’t want to have anything to do with Paramount Pictures or Bob Evans. I didn’t want to have anything to do with gangsters. I could say that because I now had a couple of bucks.”

But Paramount had caught the scent of banknotes. This was not a standoff the fat cats were likely to give up lightly. In the end, Coppola agreed to team up with Mario Puzo once more to write the script for a second movie, on. One condition: someone else would have to direct.

“[I put forward] a fabulous young director by the name of Martin Scorsese,” he told them.

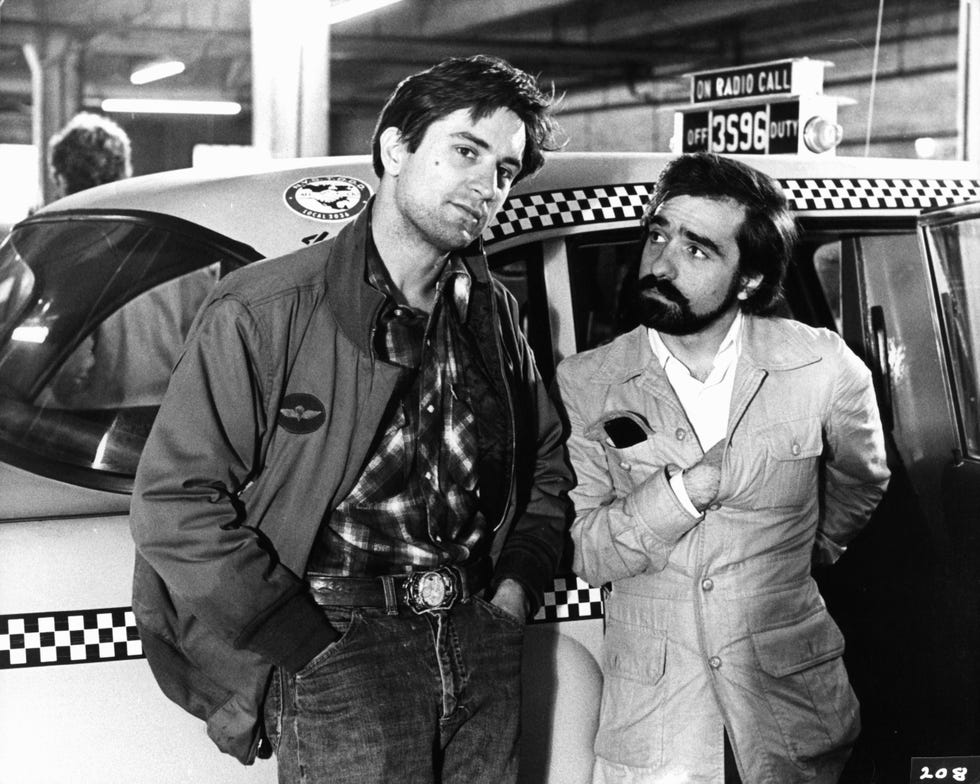

He was friends with the 29-year-old Scorsese, who’d just finished crime drama Mean Streets, and had already spoken to him about the gig.

Paramount’s response: no friggin’ way. Too young. He doesn’t have the chops.

“So I told them to forget it. Goodbye. Then the whole deal was off,” Coppola added.

Only, that scent was too strong. And in the end, Paramount made Coppola an offer he couldn’t refuse: a million dollars in his pocket, a hefty budget, complete creative control, and the chance to reunite with Al Pacino and the rest of cast (or, at least, the ones he hadn’t killed off). Faced with that kind of creative freedom, Coppola decided a return to the Corleone clan might just be worth another dance with the devil – and Hollywood.

Scorsese dodges a bullet

For Scorsese, Paramount’s lack of faith in him turned out to be a bullet dodged.

In a separate interview with Deadline, he said taking the job would’ve been a disaster. “He told me, and, honestly, I don’t think I could have made a film on that level at that time in my life, and who I was at that time,” he said. “To make a film as elegant and masterful and as historically important as Godfather II, I don’t think… Now, I would’ve made something interesting, but his maturity was already there. I still had this kind of edgy thing, the wild kid running around.”

What would Scorsese’s Godfather have looked like?

Looking back, Scorsese has said he was glad to have been denied the opportunity to direct The Godfather Part II. For him, portraying the polished politics of white-collar thuggery was a step too far from what he knew and understood. “I was more street-level,” he said. “[Growing up] what I saw around me wasn’t guys in a boardroom or sitting around a big table talking. That took another artistic level that Francis had at that point. He didn’t come from that world, the world that I came from.”

For an idea of what his interpretation would have been – short of solving String Theory and travelling to the parallel dimension where Scorsese did get the job – you needn’t look far. Eighteen years after The Godfather Part II changed mob-movie history, in 1990, Scorsese stamped his own foot on the throat of the genre. Goodfellas, by Scorsese’s own admission, is not a story set at the top of the mafia tree, but among the roots and branches. It is, as he puts it, a “street-level” underworld film.

Forget the flashy suits and big mansions. In Goodfellas, we see the Mafia from a different angle. These guys are more like low-level thugs, and the money they make isn’t nearly as impressive as they think. Their lives are chaotic and violent, like living in a constant state of fear. And because of all this danger, they can’t trust anyone. They’re surrounded by people, but ultimately alone.

If he’d cast his lens on The Godfather Part II? Well, one can only assume he would have traded the original’s sweeping grandeur for something grittier. The focus would surely shift to the lower rungs of the Corleone family – their ambitions, anxieties, and the brutal realities of their lives.

Indeed, Scorsese may well have focused his version of Puzo’s tale, not on Michael Corleone’s rise and fall, but on that of Corleone clan enforcer Frank Pentangeli. As he told Esquire in 1996: “I find Frank Pentangeli – the character played by Michael V. Gazzo – so special in The Godfather, Part II. The way he carries himself, his tone, his language, reveal someone ancient, someone who knows the Old World and sadly witnesses how it has changed. No one knows how to play the tarantella anymore, he complains. His brother’s mere presence at the congressional hearings is enough to have him recant as a government witness. It is the Old World, with its old, unmovable values, that has suddenly reappeared to remind him of an atavistic code of honour.”

What Coppola did next

Coppola ultimately returned to the director’s chair, and the rest is well documented. The Godfather Part II became not just a box-office smash but a critical darling. It expanded the Corleone saga with a prequel storyline that deepened our understanding of Vito Corleone’s rise (and Robert De Niro won an Oscar for his portrayal). It was also the first time a film was simply named a “Part II”, rather than give it a fresh title to entice punters.

“I’m the one who started the title stuff that led to films like Rocky V,” Coppola told Deadline.

Its success cemented Coppola as a powerhouse filmmaker, allowing him to explore other passion projects in his long and storied career.

What Scorsese did next

Meanwhile, Scorsese unleashed his unique energy and vision on a different kind of New York-based narrative. Instead of the smooth-operating upper echelons of the Mafia, he gave audiences a raw and often disturbing look at the life of an unhinged cabby in the gritty, unforgiving heart of the city. Taxi Driver (1976) not only cemented Scorsese’s place in cinematic history but solidified Robert De Niro as one of the greatest actors of his generation.

Scorsese would go on to explore various styles and genres, but his fascination with the darker side of human nature has been a recurring theme. His body of work includes unflinching psychological dramas like Raging Bull (1980), the black comedy of The King of Comedy (1982), religious explorations in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), and yes, eventually his own take on the world of organised crime with the epic Goodfellas (1990).

While Coppola and Scorsese both went on to create enduring masterpieces, one can’t help but wonder how their unique sensibilities would have shaped the world of the Corleones. Coppola’s sequel expanded the cinematic landscape of the Mafia with its operatic scope, while Scorsese’s work has always had a visceral, boots-on-the-pavement intensity. Their paths ultimately diverged, but that pivotal moment when their destinies nearly intertwined remains a tantalising ‘what if’ in film history.

This story originally appeared on Esquire UK

Related:

Costner, Coppola and the merits and risks of directors bankrolling their own films

Cannes film festival 2024: Which movies will we be arguing about this year?