WITH THE GRAND SLAM calendar now swinging into its most intense phase – Roland Garros’ clay battles giving way to Wimbledon’s grass-courts, before culminating at the US Open’s hardcourt theatre in September – Pat Rafter’s insights take on special significance. Few champions have navigated this gruelling trilogy with greater versatility, as we discovered first-hand earlier this year on Margaret Court Arena.

There, with Melbourne’s summer sun beating down, Rafter put our ragtag team through its paces, patiently correcting forehand glitches and demonstrating the serve-and-volley technique that became his signature. As finals-weekend crowds streamed past, more than a few spectators stopped to watch the former world No. 1 schooling scribes with the same precision that once defined his professional career.

Breathless and humbled after our on-court session, we retreat to the shade for an interview that ranges across the evolution of tennis, from wooden racquets to today’s power game. Rafter, looking remarkably unchanged from his playing days despite our exertions, continues to demonstrate the serve that twice conquered the US Open, in 1997-98. His familiar pre-serve ritual of tucking his hair behind his ears induces nostalgic smiles as the fluid motion that once unnerved opponents remains effortless and majestic, even in casual exhibition.

The connection to tennis began early for the Australian champion. “I was brought up in the country – well, the desert of [outback Queensland],” he recalls. “I’d be four or five years old, and I would take my racquet, my wooden racquet, over my shoulder and run down to the court to see if there was anyone to hit with. I [still] find it like a game of chess . . . trying to work them out, trying to understand how they play.”

As Wimbledon approaches, our Melbourne Park conversation takes on new resonance. The contrast between his elegant serve and-volley game and today’s baseline bludgeoning could hardly be more striking; for some time now, even the grass courts of Wimbledon have mostly hosted battles waged almost exclusively from the baseline.

“The game has changed,” Rafter reflects, wiping sweat from his brow. “When we go back, the game was played so much on grass, [was] so serve and volley, [played with] wooden rackets without the power. And the grass courts were pretty bad.”

With characteristic frankness, he paints a vivid picture of the sport’s physical landscape during his era. “The ball wouldn’t bounce half the time, so you wanted to take the ball in the air as much as you could. Wimbledon’s courts were the best in the world, but if you played out in Forest Hills in New York, the ball didn’t bounce. They [the courts] were soggy.”

These challenging conditions shaped not just playing styles but entire careers. For Rafter, whose attacking game thrived on the lawns of Wimbledon and the faster hardcourt surfaces of his era, today’s power baseline game represents both loss and gain – a perspective particularly relevant as the tour shifts from clay to grass.

“[Long] baseline rallies were not really part of the game. The power in the game has changed the serve and volley, and that came in towards the end of my career,” he explains. “We still had, when I was playing, four or five [top] guys serving and volleying. But now you don’t see it and it will never come back.”

Rather than lamenting this evolution, Rafter finds excitement in the modern game. Discussing American prospect Ben Shelton, whose AO semi-final loss to Jannik Sinner we’d witnessed the previous evening, his eyes light up. “He can’t do it all the time, but he can serve and volley once or twice a game. And then [in return games] he can chip and charge and come in.”

As Shelton prepares for his 2025 grass-court campaign, this ability to blend old-school tactics with modern power represents his greatest opportunity for a breakthrough at Wimbledon.

An appreciation for tennis’ evolution echoes through Rafter’s relationship with the sport’s most prestigious tournaments. While the Australian Open under Craig Tiley’s leadership has transformed into what he calls “an event that there is nothing like around the world”, each Grand Slam tournament maintains its

distinct character.

“Every one’s unique and pretty special in its own way,” he acknowledges, glancing around at Melbourne Park’s transformed landscape. “The Australian Open: what you get here, nowhere else in the world has this. The size, the theatre, the craziness, the spectacle, the music, the bands, drinking and having fun.”

But when pressed on which Grand Slam holds most significance, Rafter’s reverence for tradition shines through. “For me, the most special one is Wimbledon. I don’t know, to me, that is tennis. It’s where sort of the home of tennis was – [and] is. I always put Wimbledon as the greatest tournament there is.”

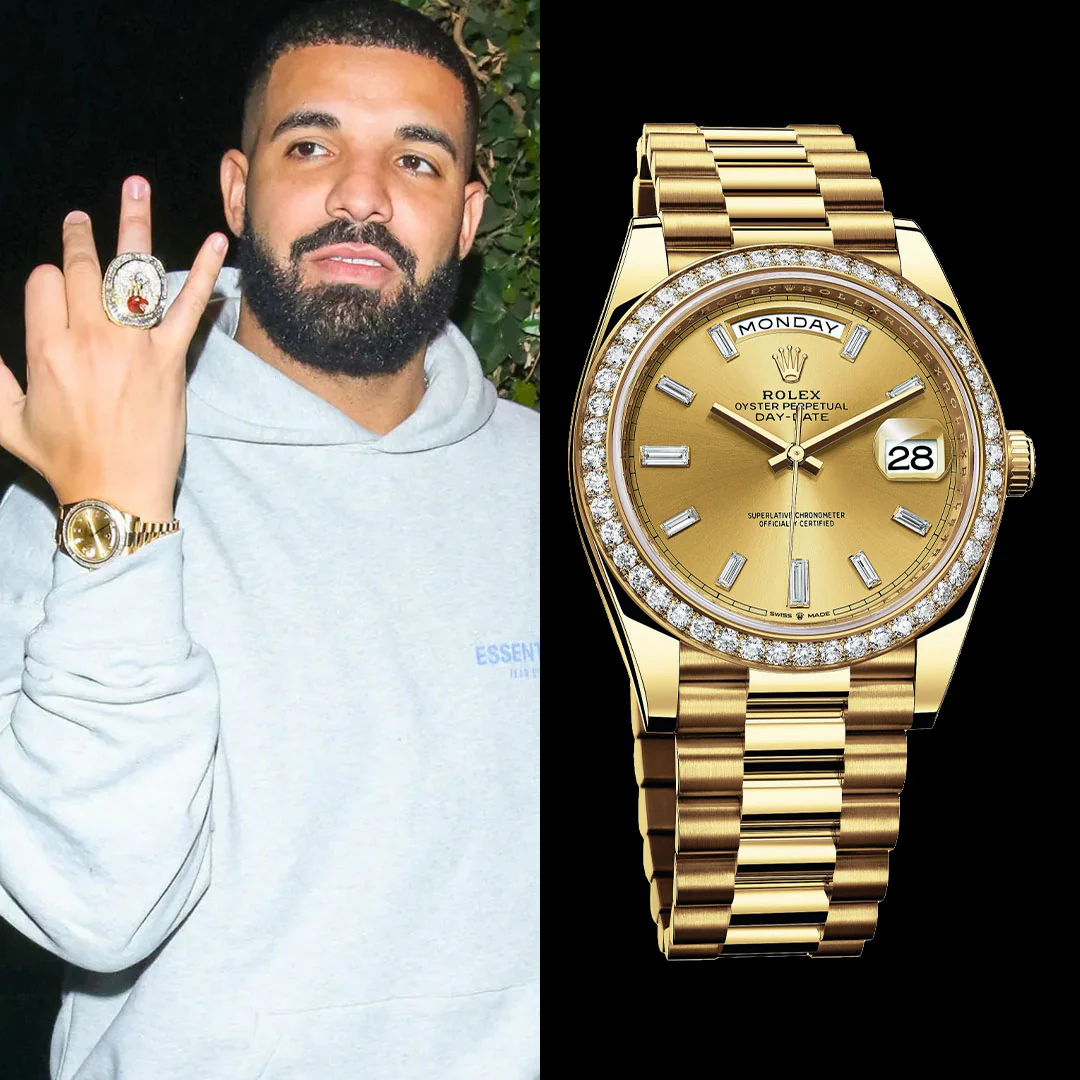

This appreciation for tradition, alongside innovation, has defined not just Rafter’s perspective but his professional relationships. For a decade now, he has maintained a partnership with Rolex, whose precision timekeeping has become as much a fixture of tennis’ greatest stages as the champions themselves. The elegant timepiece on his wrist catches the morning light as he shows us his serving motion – a partnership that will be visible courtside again when Wimbledon begins on June 30.

“When they asked me to be part of it, I was so excited,” he confesses with enthusiasm. “Even if they give me nothing, I just want to be part of Rolex.” He sees a parallel between watchmaking and tennis, though with a caveat: “The precision of making a watch is a little bit different to our precision, because everything’s so variable in tennis – the ball can bounce anywhere. It’s windy, it’s sunny, it’s raining . . . there’s more chaos in the game of tennis.”

Precision extends to Rafter’s approach to time management. “I am all about time. If I’m not five or 10 minutes early, I feel like I’m late,” he admits. “When you play tennis, you [may] have a match at 10am. If you’re not there by 10am, you can be defaulted. It’s disrespectful to your opponent and I’m big on respect for other people.”

For Rafter, career highlights occurred across the sport’s biggest venues. From his first qualifying appearance at Melbourne Park, in 1990, to his famous battles against Andre Agassi, his career spanned tennis’ grand transformation. But it was Wimbledon that captured his heart, even though he never lifted its trophy; he lost consecutive singles finals there in 2000 and 2001, to Pete Sampras and Goran Ivanišević, respectively.

The modern game’s extreme athleticism leaves even this former world-beater marvelling. “I’m in awe of how they move, how they slide on hard courts. I still don’t get it,” he admits, demonstrating a traditional split-step that seems quaint compared to today’s ultra-dynamic movement. “I don’t think we ever slid. We might have split maybe a fraction, but they’re sliding into poles.”

Asked what he might have done differently in his career, Rafter replies: “If I could have learned to relax more before I played and during the game, I would’ve been a lot more free-flowing, but I got nervous and tight because it meant so much to me.”

This intensity made him a perfect foil for opponents like Sampras, whom Rafter identified as “the coolest, calmest guy there was” under pressure. They waged several memorable battles, particularly at Wimbledon, where Sampras beat the Australian in the 2000 final. “I never won it. I wanted to win it. But I’ll take the US Open. Don’t worry, I’m very happy with two US Opens,” he chuckles.

As our January session wraps up, conversation turns to tennis’ most beloved figures. Rafter nominates Rod Laver as Australia’s most cherished champion. “Rod’s more revered now than he ever has been – and he should be.” Time, Rafter says, has burnished Laver’s achievements, notably the two Grand Slams of 1962 and 1969 – a feat that eluded even the modern-day Big Three of Federer-Nadal-Djokovic.

Now, with the tennis world turning its attention to London SW19, this respect for legacy while embracing tennis’ constant evolution is the essence of the sport’s enduring appeal. From the hard courts of Melbourne to the grass of Wimbledon, the game continues to reinvent itself while honouring its traditions – much like Rafter himself, whose serve-and-volley elegance lives on in the collective memory, while his own keen eye appreciates the power and precision of today’s game.

During this year’s Wimbledon fortnight, the sport’s pursuit of excellence will continue, measured precisely by the courtside chronometers that have witnessed generations of champions come and go – and occasionally, like Pat Rafter, leave an indelible mark on the game.

This story appears in the Winter 2025 issue of Esquire Australia, on sale now. Find out where to buy the issue here.