From painting to surfing and back again with Otis Hope Carey

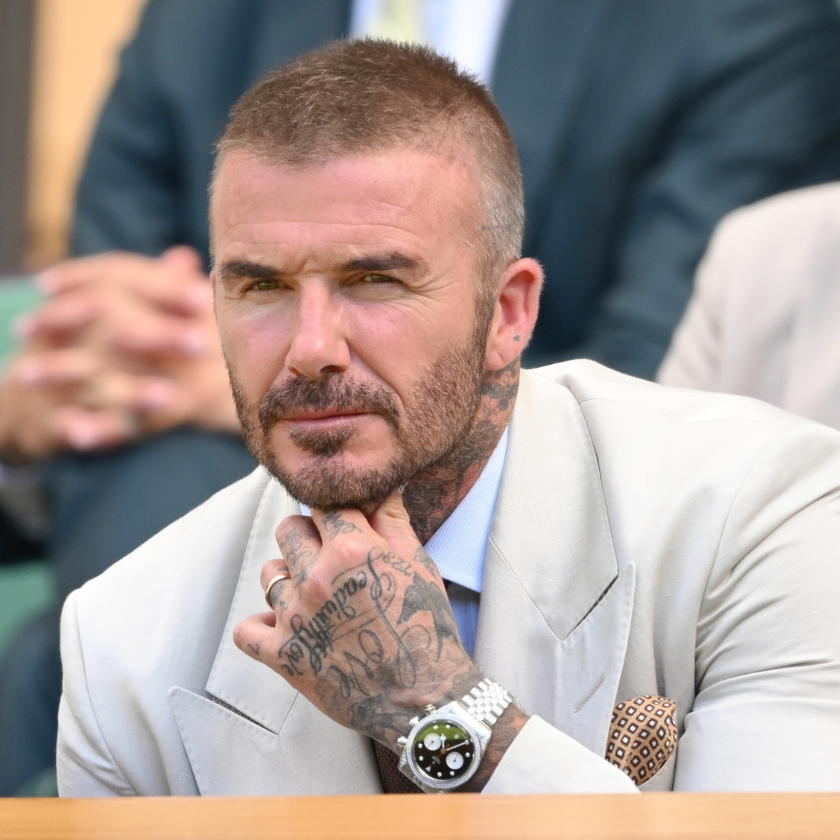

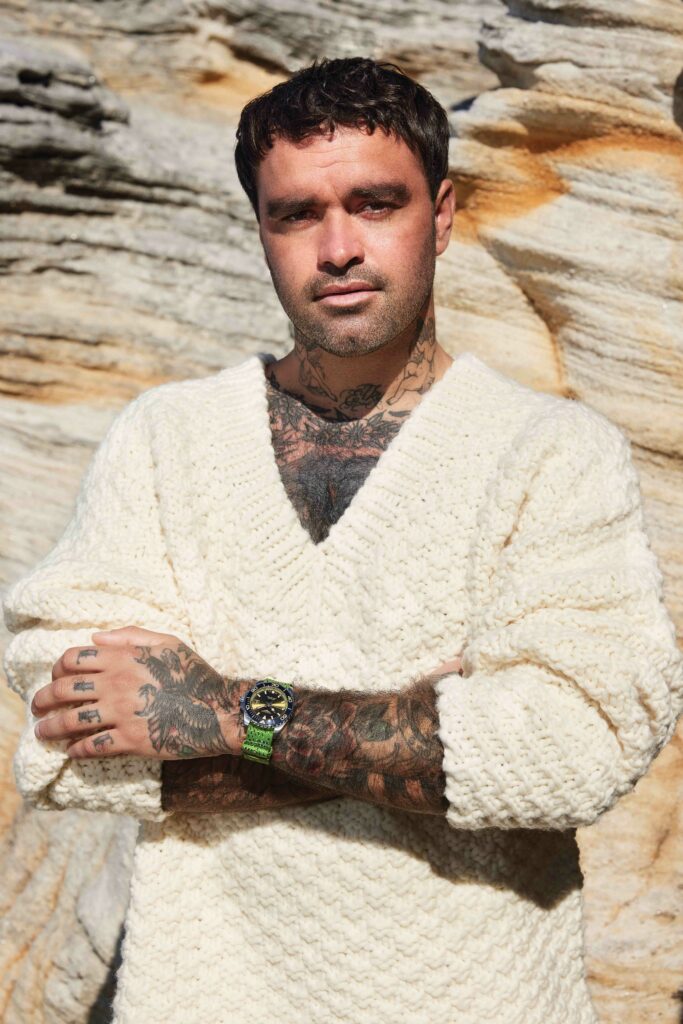

Artist and surfer Otis Hope Carey has always had a deep connection with the ocean. As he explains to Esquire, it’s there that he finds inspiration, refuge and the freedom to express himself authentically and proudly.

OTIS HOPE CAREY grew up in salt water. He was thrust into the sea at three days old. Three years later he was learning to surf on his dad’s boards. It was a place where a hyperactive kid could wear himself out. And where an adult with a mind that rarely stops could find a sense of calm.

“I just liked the freedom,” says Carey, of his early forays into the sea around Grafton in northern NSW, where he grew up. “I never did well at school. I never did well being told what to do in a confined space. Surfing was just a great outlet for me to express my freedom and exert the energy that I always had.”

Carey, who is an ambassador for watch brand Longines, is speaking to me today in a spare room at his house in Myocum, near Byron Bay on Bundjalung Country, his grandfather’s country. The ocean, or Gaagal, is the totem of his clan, the Gumbaynggirr people and growing up there was barely a day when Carey wasn’t doing something in the water, riding everything from boogie boards to long boards and anything in between. As he got better, surfing would become a creative outlet, yet although he had dreams of making it as a pro, Carey wasn’t sure he wanted it to become a competitive one. Fighting others for a wave, turning a majestic barrel into a score out of 10, that wasn’t Carey.

“I mean, it’s always been a dream to get on tour, but I’m not that much of a competitive person,” says the artist, who’s dressed today in a plain white T-shirt with tattoos creeping out the collar. “I think surfing’s such a free spirited sport. It’s just so expressive and free so I just always sat in that space rather than wanting to beat everyone in a competition.”

That annoyed his old man, who wanted to see his son assert himself on the waves. “Dad would always get shitty at me after a heat because I’d just sit there and I wouldn’t hassle anyone for a wave,” says Carey. “He’d be like ‘You should have hassled that guy. You should have snaked him’.”

Despite his lack of competitive fire, Carey’s natural ability would see him make the pro tour and win the National Indigenous Surfing Titles twice. He was living a dream yet it wasn’t quite what he thought it would be. Carey knew something was missing.

“It was weird. I always knew that I’d have a job that would allow me to express myself. I never knew what that was, but I always felt that to just ring so true. And I believed in that so much. I never thought it wouldn’t happen.”

That kind of belief in manifest destiny is rare. Carey may not have known what it was he was seeking but he suspected it would be connected to the ocean; when you’ve grown up in salt water perhaps the brine seeps into your skin. He just knew he needed something else to focus his mind when he wasn’t surfing. The answer would come to him when he was at his lowest and it wouldn’t just bring him back to the ocean but to his culture, too.

“I think I might’ve been 22 when I started struggling with depression,” says Carey, clasping his tattooed knuckles together as he speaks. “I was always talking about creative things to my therapist at the time and she was just like, ‘Maybe you should try something different, express yourself in a different way’. And so I started painting and then it made me feel better and then I dived into that on deeper levels and started to understand myself a lot more. I understood that I needed to come back to my culture and practise my cultural ways a bit more. That’s when the art turned into that contemporary Indigenous format. That’s how it all grew.”

Carey, who hadn’t painted growing up, began with tattoo-based art before he started experimenting with acrylics and creating “weird shapes” on canvas. As he’d hoped, long slabs of time spent on intricate creative work stilled his mind. It was a relief. “I’ve got a very fucking loud head, so painting allows me to focus on something that needs a lot of focus,” says Carey, whose work took off after Chris Hemsworth purchased a painting; Carey recently gave the actor a bark painting for his 40th birthday. “I think that’s why a lot of my line work, people are like, ‘Is this stencil?’ It’s got so much detail and art really helps me just pay attention to being present.”

Nowadays, Carey tries to divide his time between surfing and painting, his two hobbies complementing each other with the ocean serving as both inspiration and a canvas for his creativity. “I’ll get burnt out on one thing and then I can go back to the other and be like, ‘Oh, this is refreshing’,” says Carey, who held his first solo exhibition at Sydney’s China Heights Gallery in 2016 and was a finalist in the Wynne Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW in 2020. “I do a lot of surf trips so to have the art there to stop and slow down is comforting.”

And he’s finding ways to incorporate his hobbies into fruitful partnerships. Carey began working with Longines in 2020 and recently collaborated on a collection of special edition NATO watch straps made from recycled materials. Available in bold green, orange, blue and black, the straps complement the sunray dials of the HydroConquest collection, redesigned with an exclusive Longines GMT movement.

“The designs relate back to the ocean, Gaagal,” he says. “There’s one design there that I use symbolisms out of a traditional dance called Ngiinda Darrundang Gaagal, which means ‘I Thank the Ocean’. The other designs are from a body of work called Gaagal, The Ocean.”

And while Carey says he’s willing to explore other motifs, Gaagal will always be central to his work. “The ocean, it’s always been there when I’ve needed it most.”

Available now from Longines.

Related:

12 watches favoured by history’s most stylish men

What happens when fashion, entertainment and culture collide?